A MARKET FOR DEAD THINGS: THE GUJARI BAZAAR AND THE... URBAN REFORMATION IN AHMEDABAD A THESIS

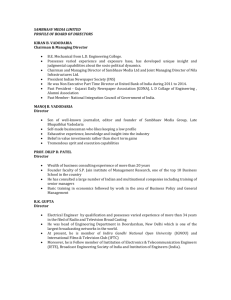

advertisement