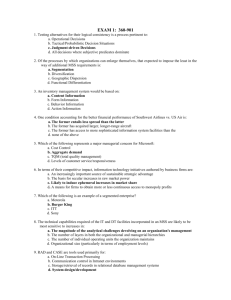

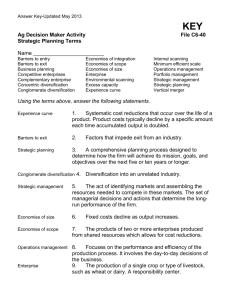

a I THE JAPAN

advertisement