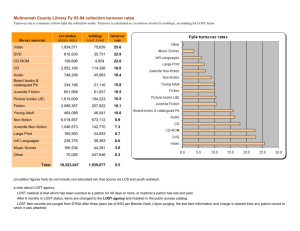

How Has CEO Turnover Changed? by

advertisement