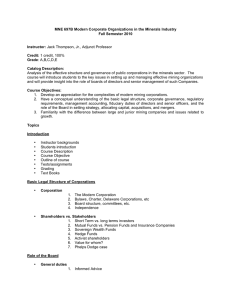

Shareholder Rights, Boards, and CEO Compensation Fisher College of Business Working Paper Series

advertisement