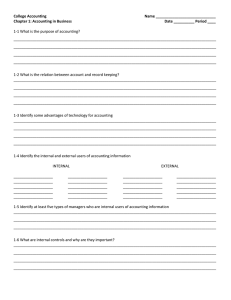

B P : E

advertisement