Indonesia’s Missing Millions: Erasing Discrimination in Birth Certification in Indonesia Cate Sumner

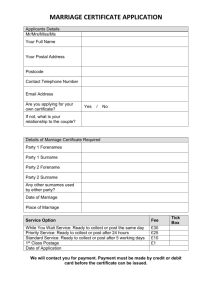

advertisement