Document 10975244

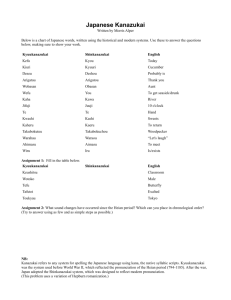

advertisement