Null Su'ojects

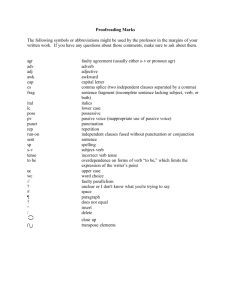

advertisement