SUCCESSION OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT: COMMUNITIES

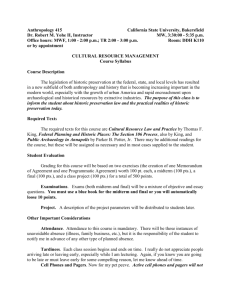

advertisement