Document 10969703

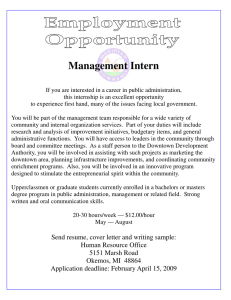

advertisement