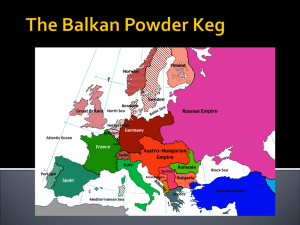

Western Balkans Annual Risk Analysis 2012

advertisement