The Effects of Induced Mood on Bidding in Random Nth-price Auctions

advertisement

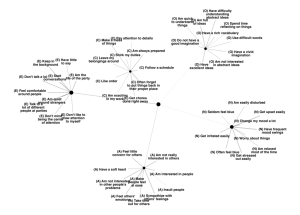

The Effects of Induced Mood on Bidding in Random Nth-price Auctions C. Monica Capra, Shireen Meer, and Kelli Lanier * July, 2006 Abstract In this paper we study whether mood affects 1) willingness to pay (WTP) and 2) the effectiveness of the demand revealing mechanism. We study decisions using a random nth price auction with induced values and homegrown values. Our data show no clear support for negative mood effects on WTP and, under some conditions, they show weak support for positive mood effects on WTP. However, mood does affect the effectiveness of the value elicitation mechanism in revealing value. Under good mood, subjects submit bids that are significantly higher than their induced values. JEL Classification: C7; C9 Keywords: Auctions, Demand revelation, Willingness to pay, Experiments, Affect, Mood. ______________________________________ * Capra, Lanier and Meer, Department of Economics, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA. We have benefited from comments from audiences at the Economics Science Association meeting in Tucson, 2005, the Southern Economic Association meeting in Washington, DC, 2005, and the Midwest Economics Association meeting in Chicago, IL, 2006. Please send correspondence to C. Monica Capra, Department of Economics, Emory University, 1602 Fishburne Drive, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA. mcapra@emory.edu (p) 404-727-6387 (f) 404-727-4639 1. Introduction In the last twenty years there has been an explosion of papers in the economics literature that try to identify and model how specific emotions such as anger, reciprocity and guilt affect decisions (see among others Frank, 1988; Rabin, 1993; Elster, 1996; and Loewenstein, 2000). However, despite there being an abundance of psychology literature pointing to the effects of people’s global affective states or moods (i.e., positive or negative feelings) on individual behavior, few economists, have investigated the effects of mood on choice.1 Indeed, psychologists believe that mood affects memory, perception and judgment, as well as choice of cognitive strategies. Bower (1981), for instance, showed that a person selectively attends to and processes information that is congruent with her current mood. Isen (2000) showed that positive affect enhances efficient reasoning and creativity, whereas negative affect enhances self-focus.2 Johnson and Tversky (1983) induced mood to show that good mood creates over-optimism revealed by a tendency to attach high probabilities to desirable events and low probabilities to undesirable ones. Thus, mood affects both the content of our thoughts and the process of thought.3 As economists, we are particularly interested in how mood affects economic interactions. In Capra (2004), for example, it was shown that positive mood enhances 1 Notable exceptions are Kirchsteiger, Rigotti and Rustichini (2006); Bosman and Riedl (2004); and Charness and Grosskopf (2000). 2 Good mood also releases dopamine, which may activate dopamine receptors in the frontal cortex and enhance alertness and reasoning. 3 Experimental and field studies in marketing also support the view that induced mood affects choices. For example, Meloy (2000) shows that creating mood by means of an unexpected occurrence (e.g. receiving a bag of candy) increases distortions in consumer choice experiments. North, Hargreaves and McKendrick (1999), in a field study, find that music-induced mood affected consumer spending at supermarkets. For a review of affect and consumer behavior also see Cohen and Areni (1991). 1 generosity and negative mood enhances reciprocity. Kirchsteiger, Rigotti, and Rustichini (2006) also showed an increase in reciprocity due to negative mood. Both of these papers studied mood effects in simple two player games. A more appealing question, however, is whether induced positive or negative moods affect competitive market interactions. Hence, in this paper we explore the notion that mood may also affect decisions in markets. Because market interactions are as complex as the market institution allows them to be, we would like to start with a simple setup. In this paper we have two objectives. First, we ask whether mood affects demand and seek to answer this question by looking at willingness to pay (WTP). The idea that positive or negative feelings could affect WTP is supported by the constructed preferences hypothesis (Payne et al., 1999; Slovic, 1995). Under this hypothesis, people are assumed to construct preferences on the spot when asked to form a particular judgment or decision, and it is believed that affect plays an important role in constructing these preferences (Slovic, 1995). The direction of the effect varies, however. If mood affects attribute attention (i.e., seeing the glass half full or half empty), then presumably positive affect may direct attention to the positive attributes of an item, increasing WTP; and negative affect may direct attention to the negative attributes, reducing WTP. In contrast, it is also possible that negative mood may generate a contradictory incentive to purchase the item, which would be supported by the affect regulation hypothesis.4 There is only one previous paper that we know of which looked at induced affective states on WTP. Lerner, Small, and Loewenstein (2004), henceforth LSL, used the Becker-DeGroot-Marshak (BDM) mechanism to elicit WTP. LSL used film clips to 4 Affective regulation predicts that people who are in a negative mood will take actions (e.g. bid more to acquire the item) to improve their moods, whereas people in positive mood will refrain from acting as a way to prevent changing their situation. 2 induce two types of negative affective states, sadness and disgust. They concluded that disgust lowered WTP, but sadness increased WTP. In contrast to LSL, to test whether induced positive or negative feelings affect WTP, we use the random nth price auction as our demand revealing mechanism (see subsection 2.1. for a detailed discussion). Our second objective is to determine whether the value elicitation mechanism itself may be influenced by mood. In Bosman and Riedl (2004), for example, induced emotional states affected bidding in a first-price auction. In addition, as mentioned above, psychologists have documented that mood affects the decision making process (Carnevale and Isen, 1986), so people may use different cognitive strategies under different moods. Consequently, differences in observed valuation, if any, may be due to mood induced “biases” in bidding rather than due to or in addition to changes in WTP.5 To control for these two possible effects, our experiment included a one shot induced value auction and a one-shot auction with homegrown values. In the induced value auctions, differences in bid dispersions are necessarily attributed to mood effects on the cognitive process. The next section explains the experimental design and procedures. Section 3 presents the results. Section 4 contains the discussion. 2. Experimental design and procedures Our purpose is to determine whether mood has an effect on WTP. We conjecture, however, that the effectiveness of the value elicitation mechanism itself may be affected by mood. Indeed, mood affects self-perceptions and judgment, which may result in a 5 In addition, our delving into the psychology literature led us to the Affect Infusion Model (AIM) derived from empirical observations and introduced by Forgas (1995). The AIM predicts that interpersonal, complex decision environments, such as competitive bidding in a random nth price auction, should be prone to mood influences. The AIM also suggests that an institution such as the BDM, which relies on individual choice, would be less likely to be affected by mood influences. 3 change in the desirability of an item (i.e., valuation), and cognition, which may result in an increase/reduction in deviations from the dominant strategy. To segregate differences in bids due to valuation from differences due to changes of cognitive strategies, our experiment consisted of a 2x3 design. We used two value conditions – induced and homegrown, and three mood treatments – positive, negative and neutral (or control). The homegrown value condition enables us to test whether willingness to pay is affected by mood, and the induced value condition helps in determining whether the value elicitation procedure itself is affected by the mood manipulation. 2.1 Choice of incentive compatible mechanism We considered several demand revealing mechanisms for the auctioned goods. These included the BDM, the second-price Vickrey auction, and the random nth-price auction. While each technique has proven successful at eliciting value, we found the nth price auction best suited to our purposes (Shogren, et al, 2001). With the BDM mechanism used by LSL, each subject submits an envelope containing his or her bid to purchase a good. After all offers are received, a price is chosen randomly from a distribution of potential prices ranging from zero to an amount anticipated to be greater than the maximum possible willingness to pay. Each subject offering to pay an amount higher than the randomly selected price pays the selected price and receives the good. An advantage of this method is that subjects are in a game of individual choice. They are not competing with other participants for the object(s) being auctioned and therefore may bid close to their true value, which is the dominant strategy. However, there is evidence that in homegrown value auctions the arbitrarily chosen upper 4 bound of the distribution of prices may affect bids. This means that, in practice, the BDM may not be incentive compatible (see Bohm, Lindén and Sonnegård, 1997 and Plott and Zeiler, 2005). Although the Vickrey auction produces more efficient aggregate outcomes than then BDM (see Noussair, et al., 2004)6, it has problems at the individual level (see List and Shogren, 1999; and Shogren, et al., 2001). In a second price Vickrey auction, overbidding may result from having too many bidders bidding for a single prize. In addition, low value bidders may “disengage” from the auction and not bid their true value. To solve this particular problem, the experimenter may be tempted to employ, for example, a sixth price auction. But this, too, raises concerns. While the low-value bidders would be enticed to bid sincerely, the high-value bidders could then become bored, because they may think they will never lose. Hence, a sixth price Vickrey auction can lead to biases among off-margin bidders. Because one of the goals of this experiment is to determine if mood affects an individual’s willingness-to-pay, we desire to provide the most robust and efficient mechanism (i.e., a mechanism through which all subjects are encouraged to bid their true values). Shogren et al. (1994) introduced a random nth price auction designed to do just that. In a random nth-price auction, each of k subjects submits a bid which is then ranked from highest to lowest. The experimenter selects a random number, n, uniformly distributed between 2 and k, and sells the unit to each of the (n-1) bidders at the nth 6 Noussair, et al., (2004) find that the BDM is subject to “…more sever biases, greater dispersion of bids, and slower convergence to truthful revelation than the Vickrey auction.” (p. 739). The authors observe differences in both biases and dispersion of bids in every period, including the first one with the Vickrey auction having fewer biases and dispersions than the BDM. With respect to differences over time, they conjecture that the shape of the payoff function is a major factor for the lower observed absolute deviation of bids from values in the Vickrey auction. 5 highest price. As shown below, payoffs for a bidder, i, are equal to zero, if her bid, bi , is less than or equal to the nth highest bid, bn . If her bid is greater than the nth highest bid, her payoffs equal her value minus the nth highest bid, bn , which is also referred to as the market price.7 ⎡ 0 πi = ⎢ ⎣vi − bn bi ≤ bn bi > bn For example, suppose there are eight subjects participating in the experiment. Each participant submits a bid for the item. The experimenter then ranks the bids and randomly selects the number 6. The five highest bidders obtain the item by paying the price of the 6th highest bidder, which is the market price. Their respective profits equal their individual redemption values less the market price; all other subjects earn zero. The dominant strategy in this auction is for each bidder, i, to bid an amount bi equal to her value, vi . To see this, consider the case where bi > vi ; this overbidding will result in no change in the subject’s payoffs if bi < bn , or if vi > bn . However, if bi > bn and vi < bn , then the subject earns negative payoffs when she could have earned zero had she bid her value. Now consider the case where bi < vi ; this underbidding will have no effect on the subject’s payoffs if bi > bn , or if vi < bn . On the other hand, if bi < bn and vi > bn , then by underbidding, the subject forgoes a positive payoff she could have earned had she bid her value. 7 In our experimental instructions, we drew a number n randomly, which determined the number of bidders who would get a unit of the good. The market price was equal to the (n+1)th bid. Please note that this implementation is theoretically identical to the one described in this subsection, but is much simpler to explain to the subjects (see the Instructions). 6 Like the Vickrey auction, the random nth price auction is incentive compatible. That is, a weakly dominant strategy is to bid your value; however, in this auction, the winning position remains a mystery until after bids are submitted, thus, it removes the competitive biases that could exist in the Vickrey auction and it gives each subject a chance to purchase the good (i.e., off margin bidders are engaged). In addition, unlike the BDM, the price is endogenously determined, which guarantees that the market-clearing price is directly related to the bidders’ values. 2.2 Timing of decisions The experiments were conducted at the Emory University experimental lab. Upon arrival, subjects were seated in isolated booths and assigned identification numbers that were used to identify their decisions for the entire duration of the experiment. Subjects were informed that they would have $15.00 credited to their accounts. All instructions were distributed to the subjects and read aloud by the experimenter throughout the experiment. Each experimental session consisted of four parts. The first part included a short survey to extract demographic information, an initial mood evaluation, and steps to ensure that participants understood the induced value random nth price auction. These steps included instructions, an exercise, to reinforce the instructions; a quiz, to determine whether the subjects thoroughly understood the experimental procedures; and a set of practice rounds, to further familiarize subjects with the auction mechanism and to inform them of the dominant strategy (i.e., to bid their true value). In the practice rounds, subjects bid for a fictitious good. After each of the three rounds, subjects were provided 7 with feedback about the market price and were asked to calculate their earnings. It was made clear that the earnings in this part were hypothetical. Mood was induced in the second part of the experiment (see next subsection for details regarding the mood induction procedures). Mood induction was followed by a self-report mood survey, where subjects used a ruler to rate how they felt. A value of 1 represented “very happy, in a very good mood” and a value of 8 represented “very unhappy, in a very bad mood.” Mood self-reports are widely used in psychology, in part because they have been shown to be correlated with behavioral and physiological measures of affective states.8 This part was eliminated in the neutral mood treatment. In the third part of the experiment, subjects participated in an induced values random nth price auction that consisted of three rounds with no feedback. 9 All subjects were given a record sheet with their randomly generated redemption values drawn from a uniform distribution between [50, 150] with one cent increments. Redemption values were private information and each subject retained the same value for all three rounds. Subjects were asked to make bids for each of the rounds, which the experimenter collected after each round and ordered from highest to lowest. Then the experimenter determined the cutoff bidder for each round at random to determine the market price. Subjects were not provided feedback about the market price after each round to avoid possible mood effects that could occur as a result of winning or losing. At the very end of 8 We are aware that self-reports can lead to biases. To begin, it is possible that subjects do not report mood states honestly; however, even if they did, internal processes may be covert and an individual may not be able to consciously access these processes (see Bems, 1965 and Nisbett and Wilson, 1977). Despite these problems, many argue that self-reports can provide approximate measures of mood. 9 The purpose of designing a three round auction with the same redemption value and without feedback is to identify those subjects who were confused as confused subjects would reveal “extremely” high variability from round to round. 8 the experiment, the experimenter revealed this information and randomly determined which of the three rounds was to count for subjects’ payments. In part four of the experiment, which was the homegrown value condition, subjects bid for a pair of movie tickets10 to a local cinema using the $15.00 that were credited to their accounts. The value elicitation mechanism used in this part was the same as with the induced value condition (i.e., one-shot auction with three trials and no feedback). Note that our experiment was designed with special emphasis to avoid methodological problems in using homegrown values that have been raised in the experimental literature (see Harrison, et al., 2004). The one-shot nature of the auction precludes the possibility of affiliated beliefs about the value or quality of the commodity. Moreover, the fact that the movie tickets are sold in the university student center and that the price is common knowledge rules out the possibility of field price censoring. Finally, we wanted to select a good that would maximize the mood effect. Indeed, one reason people have argued that bad mood leads to increased willingness-to-pay is that people in a bad mood want to “regulate” their affective state by engaging in an action that would improve their mood (e.g., acquire an item). Movie tickets provide this opportunity to subjects as they can be used to see a funny movie or any movie that they would like. Finally, the market price and the winners were announced for both the induced value and homegrown value auctions, and a survey questionnaire was distributed. The purpose of this questionnaire was to obtain some additional information from subjects about their subjective evaluation of movie tickets. Following this short questionnaire, 10 The movie tickets were sold at Emory University Student Center and were valid for an entire year at any Regal Cinemas theatre and for any movie 9 earnings were paid privately in cash and/ or movie tickets (to the winning bidders), after which the experiment concluded. 2.3. Mood Induction Procedures Mood induction procedures (MIPs) are widely used by psychologists to analyze the influence of affect on cognition, memory, problem solving, and recently by economists to analyze the effect on decision-making in games (see Capra, 2004 and Kirchsteiger et. al, 2006). While developing effective mood inducing techniques in the laboratory, one must be careful about choosing methods that are hedonically relevant, but productive of a low intensity affect. An effective mood inducer should cause a person to access thoughts that are of similar hedonic tone as the mood. Thus, most effective MIPs use recollection or imaging of emotional events. These include: 1) The Velten procedure: subjects read suggestive neutral, positive or negative statements and are asked to imagine themselves in a certain mood. 2) Hypnosis: subjects are hypnotized and asked to assume a particular mood. 3) Memory elicitation (autobiographical recollection): subjects are asked to recall and write about a sad or happy event from their lives, 4) Employment of mood-inducing audiotape or videotape, and 5) Experience of success/failure during experimental paradigms (feedback).11 We used memory elicitation and experience of success/failure in our experiments. These methods, among others, are favored by William Morris (1989) in part because they evoke a direct individual experience of the emotion. In addition, a number of studies have 11 A number of psychologists have also used unexpected gifts to induce positive mood. For example, Isen and Geva (1987) gave subjects a small bag of candy. They showed that gifts are effective at making people feel elated. We disfavor this method, however, as it disrupts the relationship between experimenter and subject. 10 discovered strengths of these methods when looking at the efficacy of numerous procedures. For example, a meta-analysis on the effectiveness and validity of MIPs by Westermann et al. (1996) finds that for the induction of negative mood states, Memory elicitation and Feedback are the most effective methods. They find that the effects of using videotapes or films are the strongest in inducing both positive and negative affect, but only when subjects are explicitly instructed to enter into the specified mood state. However, there is considerable debate as to the validity of asking subjects to assume a mood state due to the demand effects (i.e., subjects pretend to be in the mood state to comply with the demand of the experimenter) and thus the effectiveness of these procedures can be overestimated. Finally, Capra (2004) also successfully used written autobiographical recollections and the experience of success and failure in game experiments. So, we found convincing support for both the feedback and the written autobiographical recollection MIPs. 2.4. Subjects and earnings In total 68 subjects, mostly undergraduate students from Emory University, participated in 9 experimental sessions each with 8-7 subjects; no participant attended more than one session. There were 3 sessions for each mood treatment corresponding to positive, neutral and negative affective states.12 The subjects were recruited from economics classes and also by posting announcements on an electronic university-wide message board. Participants were from a variety of majors including economics, law, and humanities. Upon arrival, subjects were credited $15 to their accounts, which they would 12 Instructions for all treatments were identical except for the mood manipulation section, which was excluded in the control (neutral mood) treatment. The complete instructions are attached in the Appendix. 11 later use to bid in the auction. On average, subjects earned about $15, and the auction winners from part 3 won movie tickets in addition to the money. Each experimental session took a little over one hour. 3. Results Self-reports suggest that mood induction was successful for both the negative and positive mood treatments. The mean mood rates are 2.60, 3.15, and 4.37 in the positive, control (neutral mood) and negative mood treatments, respectively. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of scores for the overall emotional states after mood induction. It can be seen that subjects in an induced positive mood report a positive emotional state much more frequently than subjects in an induced negative mood. In addition, using the KruskalWallis test, we reject the null hypothesis of no difference in self-reported mood across the three treatments (p <0.01). A pair wise comparison rejects the null of no difference between self-reports in the negative and positive mood treatments and between the negative and control treatments. Thus, at least as is reflected in the self-reported scores, mood induction was successful. 0 2 4 6 8 Figure 1 – Distribution of Self-Reported Mood Scores after Mood Induction (8=very bad, 1=very good) Positive Control Negative 12 3.1. Results of the Induced Value Auction In the induced value condition, all subjects were given their randomly generated redemption values drawn from a uniform distribution over the range [50, 150] with one cent increments and were asked to place their bid in three rounds without feedback (subjects’ values remained the same). The average bid (averaged across rounds) is referred to as AvBid. Table 1 contains the summary statistics of the induced value condition. Table 1 – Summary Statistics Summary Statistics AvBid (US cents) Value (US cents) AvBid – Value AvBid-to-Value Positive Mean (S.D) 104.51 (32.91) 94.29 (33.04) 10.22 (27.65) 1.18 (0.47) Control Mean (S.D) 99.58 (36.44) 97.85 (34.37) 1.73 (9.41) 1.02 (0.13) Negative Mean (S.D) 101.09 (35.56) 99.04 (34.45) 2.04 (13.99) 1.03 (0.16) The results show the mean average bid (mean AvBid) to be the highest for the positive treatment (104.51). In addition, the mean dispersion or AvBid – Value, which is calculated as ∑ j [ avg .b j − v j ] , where avg.bj is player j’s average bid and vj is player j’s redemption value, is highest under positive mood (10.22). Finally the AvBid-to-Value ratio shows overbidding under all mood conditions, but subjects, on average, overbid by 18% when under positive mood. Figure 2 below shows the percentage of actual bids that are less, equal or greater than the redemption values.13 In the positive mood treatment 43.1% of the bids were higher than the value as compared to 15.9% in the negative mood treatment. Interestingly, under the induced positive mood treatment, 40.3% of the bids are perfectly 13 Here we used the data from each bid round. Recall that there were three bid rounds without feedback for each individual with the same induced value. 13 demand revealing compared to 55.0% and 60.9% under the control and induced negative moods, respectively. This result is consistent with the psychology literature that suggests that negative mood enhances focus.14 Using the Chi square test, we reject the null that there is an equal proportion of subjects who bid lower than, equal to or higher than their value in each of the treatment groups (p=.008). We also reject the null of equal proportions in the pair-wise comparisons between the positive and negative and positive and control treatments (p=.002 and .058, respectively). Figure 2 – Frequency of Actual Bids Relative to Redemption Values 23.3% B>V 55.0% B=V B<V 15.9% 43.1% 60.9% 40.3% 16.7% 21.7% 23.2% Positive Control Negative Figure 3 shows the average deviations from induced values for each subject under the three mood conditions. The diagonal line represents all bids that equaled the induced value. The figure depicts individual differences across treatments. Clearly, positive mood generates greater distortions as compared to the control and negative mood treatments. 14 There is evidence that people in negative moods focus their attention at a relatively detailed level. Lassiter and Koenig (1991; as described in Emotion and Cognition – a lecture by E. T Pritchard) found that depressed people counted more actions in a short film clip than non-depressed people, which suggests that the depressed people made more detailed observations. Also refer to Norman (2002) 14 Figure 3 – Individual Average Bid Deviations from Induced Value P o si ti v e M o o d 200 Mean Bid 150 100 50 0 0 50 100 R e d e m p tio n V a lu e 150 200 150 200 150 200 C o n tr o l 200 Mean Bid 150 100 50 0 0 50 100 R e d e m p t io n V a lu e N e g a ti v e M o o d Mean Bid 200 150 100 50 0 0 50 100 R e d e m p t io n V a lu e To further test for differences in dispersions created by mood, we used the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. We conclude that differences in average absolute deviations under positive mood are greater than those under negative mood (p=0.070) and larger than those under the control treatment, but only weakly so (p=0.144). Finally, we were interested in determining whether deviations from the dominant strategy were more likely to occur among the subjects with very high or very low induced values. We divided our subjects into two groups: extreme value bidders and non-extreme 15 value bidders. 15 Table 2 below shows the average deviations from bids in these two groups. The top number in each row shows the average squared deviation while the bottom number is the average absolute deviation. It can be seen that the average squared and average absolute deviations are higher in the positive mood treatment than the negative mood treatment. This result holds true irrespective of whether we look at the pooled observations or categorize them by extreme/ non-extreme value subjects. Table 2 – Average Deviation of Bids from Redemption Values (mean squared deviations on top & mean absolute deviations on bottom – standard deviations in parentheses) Positive Mean (SD) 837.04 (2158.91) 14.89 (25.34) Mean 91.60 5.40 (SD) (188.11) (8.11) Negative Mean (SD) 191.64 (417.41) 7.32 (12.01) Players with extreme values 1891.92 24.05 (3704.17) (39.15) 95.01 5.21 (175.36) (8.81) 214.76 7.46 (454.15) (13.49) Players with non-extreme values 402.62 11.12 (931.34) (17.22) 89.32 5.53 ( 203.80) (8.01) 179.30 7.24 (412.56) (11.66) Pooled data Control As a final analysis for the induced value condition, Table 3 shows the aggregate economic losses associated with this auction. We divided the total economic losses into two categories: amount “lost”, which includes the aggregate losses that accrued from subjects winning the auction despite having values which were lower than the market price – in other words, losses from subjects who should not have won, but did. The amount “forgone” represents the aggregate economic losses from subjects who did not win the auction although their values were higher than the market price – in other words, subjects who should have won, but did not. The last two rows in the table represent the 15 Extreme redemption values were defined as those values that were above 140 or below 60. While this is an arbitrary definition, it is one that seems reasonable given that the redemption values are drawn from a [50, 150] distribution. 16 average lost or forgone amounts by round and the percentage of the economic losses due to overbidding (realized losses) and underbidding (forgone amounts). The values are all in US cents and entries that have a star next to them represent losses or forgone amounts actually incurred by the subject during the experiment as they were compensated for one randomly chosen round. If the auction mechanism is not affected by mood in terms of how well it reveals values, then we would expect total losses in each of the mood treatments to be approximately equal to those in the control treatment. However, we see that this is not the case. Total losses in the positive mood treatment averaged about 38 cents, with most money being lost due to overbidding. Clearly, at the aggregate level, positive mood subjects are subject to more errors, but errors are biased upwards. In contrast, in the negative treatment, total losses averaged about 15 cents, with most losses being forgone amounts due to underbidding. Finally, in the control treatment (neutral mood), average per round losses were the smallest suggesting that a larger number of subjects deviated from bidding their values, but they did so by smaller amounts. Table 3 – Table of Economic Losses – all sessions and all rounds Round 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 Lost 35 45 *17 0 *0 62 46 96 *44 Avg./round 38.33 98% Positive Control Negative Forgone Total Lost Forgone Total Lost Forgone Total 7 42 *0 *0 *0 28 21 49 0 45 0 10 10 *0 *0 *0 *0 *17 0 0 0 4 21 25 0 0 0 0 0 15 0 15 *1 *1 *0 *0 *0 *0 *48 *48 0 62 23 0 23 1 0 0 0 46 *0 *0 *0 0 0 0 0 96 0 0 0 *0 *0 *0 *0 *44 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.89 2% 39.22 2.56 70% 1.11 30% 3.67 5.33 35% 10.00 65% 15.22 * = round that counted towards subjects’ earnings 17 To summarize our results, we observed significant differences in the percentage of subjects who exactly bid their values across mood conditions. Negative mood generated the most number of demand revealing choices. In terms of efficiency, however, negative mood did not perform as well as the neutral mood (i.e., control treatment). Under negative mood people incurred more economic losses and bid dispersion was higher than under neutral mood, but these differences were not statistically significant. Positive mood generated large biases in decision making; average subject bids were about 18% above the induced values and bid dispersion was significantly higher than that under neutral mood. On average, positive mood generated an economic loss for the subjects 10 times and 3 times larger than neutral and negative moods, respectively. Thus, positive mood generated large distortions in bidding. The next subsection presents the results from the homegrown value auction to determine mood induced differences in WTP. 3.2. Results of the Homegrown Value Auction This section presents the results for the homegrown16 value auctions. In this value condition, subjects were asked to bid for a pair of movie tickets to a local cinema. This auction was one-shot and involved three rounds without feedback. One of the rounds was randomly chosen at the end of the experiment to count towards earnings. It is important to mention here that there are a number of criticisms in the experimental literature associated with the use of homegrown values. These are: 1) value and belief affiliation, 2) learning effects and 3) degree of substitutability of the product.17 As discussed briefly in 16 The term “homegrown” refers to values that are not induced. See Harrison et al (2004) for a thorough discussion on the methodological problems with homegrown value auctions designs. 17 18 Section 2.2, these problems were anticipated and dealt with in the design of the experiment. The one-shot nature of the auctions in our experiment precludes value and belief affiliations. Learning effects are not an issue with our design because prices are revealed at the end of the experiment preventing subjects from getting feedback between rounds. We are not concerned about confusion because our instructions revealed the dominant strategies and our experiments included a practice exercise and trial rounds with induced values where subjects became aware of the dominant strategy (see section 2). Finally, the possibility of field-price censoring is evident in our setup as the item we chose (movie tickets) has perfect substitutes in the field. 18 However, by choosing generic tickets19 that are sold on campus, we tried to minimize the uncertainty about the value of the item. 3.2.1. Aggregate Data: The distribution of average bids by treatment is shown in Figure 4. In addition, Table 4 below reports the summary statistics for the homegrown value auctions. The summary statistics of the bid distributions shows that the average bids for subjects under the positive mood treatment is lowest ($5.91), followed by the negative mood treatment ($6.40), and the average bids in the control treatment is the highest ($8.28). However, an analysis of variance reveals that these differences in means are not statistically significant (p=0.277).20 18 Hanemann et al. (1991) and Shogren et al. (1994) discuss problems associated with the degree of substitutability of the product. 19 The tickets that were auctioned off were purchased at the Emory University student center at a fixed discounted price of $6.50 per ticket. This value is common knowledge amongst students. 20 A pair wise analysis of variance between treatments also shows no statistical difference in the bid distributions. These results are further supported by a median test (p=0.6546 for Control vs. Negative Mood and p=0.3640 for Control vs. Positive Mood). 19 0 5 10 15 Figure 4 – Distribution of Average Subject Bids (Homegrown Value Auction) Positive Control Negative Table 4 – Summary Statistics for Homegrown Value Auctions Summary Statistics Bid Mean (SD) Bid Median Positive Mood 5.91 (4.77) 5.06 Control 8.28 (5.42) 10.00 Negative Mood 6.40 (4.95) 5.00 This analysis assumes that subjects bid their values, and that the values are affected by mood. However, as the previous subsection showed, mood affects the decision process, particularly for the positive mood treatment. Given that in the induced value condition, positive mood was seen to affect bids, the bid data under this mood treatment must be taken with caution. To provide a fairer test for the effects of mood on WTP, we decided to drop the observations from the good mood sessions and aggregate mood scores across the neutral and negative mood treatments only. The results of a two sided Tobit regression using the control and negative mood data with mean bids as the dependent variable and self-reported mood as the independent variable suggest that mood 20 has no effect on WTP for movie tickets.21 We further tested for the existence of “extreme mood effects” on WTP. That is, we pooled the data across the two treatments and stratified them by self-reported mood. We considered three groups, those people who self-reported excellent mood (scores of 1-2), those under neutral mood (scores 3-4), and those with really bad mood (score of 6-8). We found no extreme mood effect (see the Appendix for Tobit regression results). Finally, we decided to stretch our data a little more in search for a mood effect on WTP. Table 5 provides summary statistics for the three mood conditions under the assumption that subjects’ bids were above or below their true value by the exact same magnitude as in the induced value condition. For example, if an individual overbid by say10% in the first part of the experiment (i.e., induced values), the bid in the homegrown value part was assumed to be 10% higher than his true value; thus, we would adjust the bid downward to neutralize the bias. While our bias adjustments are arbitrary and there is no proven support for thinking that the same biases happen when people bid for movie tickets, this exercise provides a kind of robustness check for mood effects. Indeed, our analysis of variance shows that the only statistically significant differences in means happen between the control and positive mood treatments (p=0.057). When we consider the fact that positive mood does impact the decision process and attempt to neutralize that impact, we can show that positive mood lowers WTP as compared to a neutral mood condition. However, after using this adjustment and in contrast to LSL, we observe no negative mood (sadness) effect on WTP. 21 We also regressed mean bids against relative mood. The mood data was divided into two groups. One group included scores that were § 4 and the other included scores that were > 4 in the Likert scale. We observe no differences in the results. 21 Table 5 – Summary Statistics for Homegrown Value Auctions + Errors Assumed from overbidding or underbidding Summary Statistics Bid Mean (SD) Bid Median Positive Mood 5.05 (4.69) 4.39 Control 8.04 (5.41) 7.76 Negative Mood 6.40 (5.32) 5.00 To summarize, given that mood generates biases in decision making, it is hard to isolate the mood effects on WTP. This is especially true for positive mood. Negative mood results in biases no different from the control treatment (i.e., neutral mood); thus, a comparison between WTP under negative and neutral mood is possible. We observe, however, no mood effects on WTP. Finally, assuming that in the homegrown values auction subjects’ bids deviate from their true value the same way they do under the induced value condition, we observe that positive mood negatively affects WTP. 4. Discussion Psychologists and economists alike have shown that specific emotions impact decision making. While psychologists have also studied extensively the impact of global moods on subjects’ actions, this paper is only the second within the field of economics to attempt to better understand how an overall positive or negative feeling can influence someone’s WTP. We believe a better knowledge of the impact of emotions on market decisions is valuable information, and the validity of our assumption regarding its importance is supported by the constructed preferences hypothesis (Payne et al., 1999; Slovic, 1995). If preferences are stable and well-defined, then they should not alter with changing moods. However, the constructed preferences hypothesis posits that individuals develop their values and preferences on the spot when asked to form a particular judgment or to make a 22 specific decision. Values are not merely “uncovered” when elicited, they are, at least in part, constructed at that time, and this constructive process is influenced by both mechanistic as well as affective considerations. It is therefore implied that induced mood should affect people’s WTP for an item. However, exactly how affect should influence WTP is not clear. If mood in fact affects the attention an individual places on attributes of an item, then a positive affect may direct attention to the positive attributes of the item and conversely, a negative affect may direct attention to the item’s negative attributes. A preliminary hypothesis based on this information alone may lead one to believe that by inducing a negative mood we would see a decreased WTP and by inducing a positive mood, we would see an increased WTP. However, other factors also come into play. For example, affect regulation hypothesis (Cohen and Andrade, 2004) suggests that a negative mood may initiate an incentive to purchase an item in an effort to change the individual’s situation; and thus her mood from bad to good; whereas a person in a positive mood will be satisfied to maintain the status quo. Taking this theory into account we might see an increase in the WTP resulting from an induced negative mood, and little or no change in WTP resulting from the induced positive mood. We approached this project with the intent to determine whether mood affects WTP. Like LSL, would we find that sadness (which can be indicative of a bad mood) lowers WTP? In beginning our research; however, we also considered the possibility that mood may affect bidding behavior in the auction. Previous research has shown that people in a negative mood are prone to pay more attention to detail and focus more critically on a task than do people in a neutral or positive mood (Martin and Clore, 2001) 23 In this regard, we became specifically interested in whether or not mood would impact the ability of a subject to reveal the value she places on the item. Consequently, we uncovered a second objective: to determine if the value elicitation mechanism we use is influenced by mood. After successfully inducing positive or negative moods (depending on the treatment), we were able to determine that while being in a negative mood does not impact the effectiveness of the value elicitation mechanism, being in a positive mood tends to make the random nth price auction (which has been proven successful in revealing WTP) less demand revealing; we find that subjects in a good mood overbid about 18% of their induced value. Perhaps subjects who have been induced into a positive mood have become less detail oriented and do not focus on the demandrevealing task or perhaps positive mood enhances competitive drives in people making them prone to overbidding as predicted by the Affect Infusion Model (Forgas, 1995). With the knowledge that (positive) mood does generate biases in decision making, we turned back to our original question: Does mood impact WTP? By auctioning pairs of movie tickets to a local cinema, we saw that compared to a neutral mood, a negative mood generates no change in WTP, and when taking into account the bias that mood creates in the decision-making capabilities, we determine that only positive mood affects WTP. We can interpret these findings to mean that while a negative mood may imply a lower WTP due to attention placed on negative attributes, it also encourages an individual to act in such a way as to alter their mood which implies a higher WTP, and the overall impact of these two effects results in no change in WTP. Alternatively, we can interpret the finding as suggesting no mood effects on WTP. 24 When biases from decision making are adjusted, we find that positive mood lowers WTP as compared to the neutral mood treatment. Perhaps one explanation for this result lies in the affect regulation hypothesis. If subjects in a good mood refrain from acting in order to maintain the status quo (which here means not having a movie ticket) and yet they are asked to participate in the auction as part of the experiment, then perhaps they would bid lower in an attempt to not win a ticket and therefore not change their situation. Concrete explanations for this result remain to be determined; however, overall we find little support for the idea that affect plays an important role in the construction of preferences, specifically in willingness to pay. 25 References Becker, Gordon. M.; DeGroot, Morris H. and Marschak, Jacob D. “Measuring Utility by a Single-Response Sequential Method.” Behavioral Science, 1964, 9(3), pp. 226-232. Bem, Daryl J. “An Experimental Analysis of Self-Persuasion” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 1965, 1(3), pp. 199-218. Bohm, Peter; Lindén, Johan and Sonnegård, Joakin. “Eliciting Reservation Prices: Becker-DeGroot-Marschak Mechanisms Vs. Markets.” The Economic Journal, 1997, 107(443), pp. 1079-1089. Ronald Bosman and Arno Riedl. Emotions and Economic Shocks in a First-Price Auction: An Experimental Study, 2004. University of Amsterdam Working Paper. Bower, Gordon H. “Mood and Memory.” American Psychologist, 1981, 36(2), pp. 129148. Capra, C. Mónica. “Mood-Driven Behavior in Strategic Interactions.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 2004, 94(2), pp. 367-372. Carnevale, Peter J.D. and Isen, Alice M. “The Influence of Positive Affect and Visual Access on the Discovery of Integrative Solutions in Bilateral Negotiation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1986, 37(1), pp. 1-13. Charness, Gary; and Grosskopf, Brit. “Relative Payoffs and Happiness: An Experimental Study.” Working paper, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain, January 2000. Cohen, Joel B. and Andrade, Eduardo B. “Affective Intuition and Task-Contingent Regulation.” Journal of Consumer Research, 2004, 31(2), pp. 358-367. Cohen, Joel B. and Areni, Charles S. “Affect and Consumer Behavior,” in Thomas S. Robertson and Harold H. Kasserjian, eds. Handbook of Consumer Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1991, pp. 188-240. Elster, Jon. Rationality and the Emotions, The Economic Journal, 1996, 106 (438): 1386-1397 Forgas, Joseph P. “Mood and Judgment: The Affect Infusion Model (AIM).” Psychological Bulletin, 1995, 117(1), pp. 39-66. Frank, Robert H. Passions within reason, New York: W. W. Norton, 1988. 26 Hanemann, W. Michael, “Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept: How Much Can They Differ?” American Economic Review, 1991, 81(3), pp. 635-647. Harrison, Glenn W; Harstad, Ronald M. and Rutström, E. Elisabet. “Experimental Methods and Elicitation of Values.” Experimental Economics, 2004, 7(2), pp.123-140. Isen, Alice M. "Positive Affect and Decision Making." In M. Lewis and J. M. HavilandJones, eds. Handbook of Emotions. 2nd Edition, New York: Guilford: 2000, pp. 417-435. Isen, Alice M. and Geva, Nehemia. “The Influence of Positive Affect on Acceptable Level of Risk: The Person with a Large Canoe Has a Large Worry.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1987, 39(2), pp. 145-154. Johnson, Eric J. and Tversky, Amos. “Affect, Generalization and the Perception of Risk.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1983, 45(1), pp. 20-31. Kirchsteiger, Georg; Rigotti, Luca and Rustichini, Aldo. “Your Morals Might Be Your Moods.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2006, 59(2), pp. 155172. Lerner, Jennifer S.; Small, Deborah A. and Loewenstein, George. “Heart Strings and Purse Strings – Carryover Effects of Emotions on Economic Decisions.” Psychological Science, 2004, 15(5), pp. 337-341. Loewenstein, George. “Emotions in Economic Theory and Economic Behavior.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 2000, 90(2), pp. 426-432. List, John A. and Shogren, Jason F. “Price Information and Bidding Behavior in Repeated Second-Price Auctions.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 1999, 81(4), pp. 942-949. Martin, Leonard L., and Clore, Gerald L. Theories of Mood and Cognition: A Users Handbook, Nahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates, 2001. Meloy, Margaret G. “Mood-Driven Distortion of Product Information.” Journal of Consumer Research, 2000, 27(3), pp. 345-359. Morris, William N., Mood: The Frame of Mind. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1989. Norman, Don. “Emotion & Design: Attractive Things Work Better.” Interactions, 2002, 9(4), pp. 36-42. Nisbett, Richard E. and Wilson, Timothy DeCamp. “Telling More Than We Can Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes.” Psychological Review, 1977, 84(3), pp. 231-259. 27 North, Adrian C.; Hargreaves, David J. and McKendrick, Jennifer. “The Influence of In-Store Music on Wine Selections.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1999, 84(2), pp. 271-276. Noussair, Charles; Robin, Stephanie and Ruffieux, Bernard. “Revealing Consumers’ Willingness-to-Pay: A Comparison of the BDM Mechanism and the Vickrey Auction.” Journal of Economic Psychology, 2004, 25(6), pp. 725-741. Payne, John W.; Bettman, James R. and Schkade, David A. “Measuring Constructed Preferences: Towards a Building Code.” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1999, 19(1), pp. 243-271. Pritchard, Evan.T, “Emotion and Cognition,” Lecture – website: http://io.uwinnipeg.ca/~epritch1/emocog.htm Plott, Charles R. and Zeiler, Kathryn. “The Willingness to Pay-Willingness to Accept Gap, the ‘Endowment Effect,’ Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures for Eliciting Valuations.” American Economic Review, 2005, 95(3), pp. 530-545. Rabin, Matthew. "Incorporating Fairness into Game Theory and Economics." American Economic Review, 1993, 83(5), pp. 1281-1302. Shogren, Jason F.; Fox, John A.; Hayes, Dermot J. and Kliebenstein, James B. “Bid Sensitivity and the Structure of the Vickrey Auction.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 1994, 76(5), pp. 1089-1095. Shogren, Jason F.; Margolis, Michael; Koo, Cannon and List, John A. “A Random nth-price Auction.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2001, 46(4), pp. 409-421. Shogren, Jason F.; Shin, Seung Y.; Hayes, Dermot J. and Kliebenstein, James B. “Resolving Differences in Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept.” American Economic Review. 1994, 84(1), pp. 255-270. Slovic, Paul. “The Construction of Preference.” American Psychologist, 1995, 50(5), pp. 364-371. Westermann, Rainer; Spies, Kordelia; Stahl, Günter and Hesse, Friedrich W. “Relative Effectiveness and Validity of Mood Induction Procedures: A Meta-Analysis.” European Journal of Social Psychology, 1996, 26(4), pp. 557-580. 28 Appendix: Tobit Regression Results Two-sided Tobit Regression with Negative and Neutral Mood Observations Mean Bid Positive Mood Negative Mood Coefficient (S.E) 1.37 (3.74) -0.22 (3.78) P >|z| 95% Confidence Interval 0.714 -5.96 8.70 0.95 -7.64 7.19 Two-sided Tobit Regression with Negative and Neutral Mood Observations Testing for Extreme Mood Effects Mean Bid One-two Three-four Six-eight Coefficient (S.E) 2.24 (1.41) 1.24 (1.57) 4.46 (5.01) P >|z| 95% Confidence Interval 0.112 -0.52 4.99 0.43 -1.84 4.31 0.37 -5.37 14.28 29 Note: The instructions below are not meant for publication. These instructions have been appended to facilitate the referees’ evaluation of the manuscript. Instructions General Instructions: This is an experiment in the economics of decision-making. The instructions are simple, and if you follow them carefully, you might be able to win a product and earn money. The experiment consists of several parts. In each part you will be asked to respond to a series of survey questions or make decisions. At the beginning of the experiment, you will be assigned an ID number. Only the ID number, not your name, will be used to identify your answers and decisions. Earnings: We will now credit to you $15.00 for participating in this experiment. As you will learn later, you will be able to use this money to win a product. You will also have an opportunity to earn additional money. Your final earnings, which may or may not include the product, will partly depend on your own decisions, on others’ decisions and on chance. The responses to the survey questions do not affect your earnings. Finally, the final earnings in dollars and the product that you may win during this experiment will be given to you privately at the end of the experiment. Please do not communicate with other participants, and keep silent during the experiment. If you have a question, raise your hand and one of the experimenters will approach you. We will now start with the first part of the experiment. At this time, do you have any questions? ---------------------page break ----------------------Part 1: Survey questions ID # _______________ Your ID number is written in the upper-right side of this sheet. Please answer the following questions: 1) What is your Gender? Male Female 2) What is your Class? Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior 3) What is your major (intended major, or academic interest – list only one)? __________________ 4) Rate how you feel on the following scale by putting an X anywhere on the ruler below: ‘ Very happy/ in a very good mood Neutral Very unhappy/ in a very bad mood ------------------------------page break---------------------------- 30 Part 2: Decisions ID#: _________ Instructions: Your ID number is written in the upper-right side of this sheet. In this part you will participate in three rounds of a sealed-bid auction. Please pay close attention to the rules of the auction. The purpose of this part is to help you understand the auction format. All earnings in this part are hypothetical. Auction Rules: There will be three rounds of this auction. In each round, we will auction a random number of units of a fictitious good that we will call good “X”. The number of units to auction will be determined by drawing a numbered ping pong ball from this urn. So, if we draw the number 3, it means that 3 units of the good will be auctioned. Similarly, if we draw the number 2, only 2 units will be auctioned. The maximum number of units to auction is 8. You will participate in the auction together with the 7 other participants. The value of X to you is called “your redemption value.” “Your redemption value” represents how much you value a unit of X in US cents. Your redemption value was determined randomly using a random number generator. Any value between 50 and 150 was equally likely. All other participants also receive their own random redemption values. Since each person receives his/her own random redemption value, your redemption value will typically be different than those of other players. Now pay attention to the Record Table attached to these instructions on page 5. This table contains two columns and four rows. During each round, “YOUR REDEMPTION VALUE” will correspond to the randomly generated number you have been provided. How to bid: In each round you will bid for the unit “before” learning how many units are available in the auction; that is, before we draw the numbered ping-pong ball. Please pay attention to Record Table on page 5. You may submit a bid for one unit of X by filling out the second row of the second column that corresponds to “YOUR BID”. Once you have filled out your form, the experimenter will approach your table and record your choice. Once all participants have submitted their bids, the experimenter will order bids from highest to lowest. How to obtain a unit of X: After all participants submit their bids, the experimenter will randomly choose the number of units to be auctioned using the ping-pong balls as explained above. This will also determine the cut-off bidder and the market price. Suppose that we draw a ping-pong ball with the number 3 written on it, the cut-off bidder is the person whose bid ranks fourth when all bids are ordered from highest to lowest (highest bid ranks first). After the cut-off bidder is determined, the experimenter will write the price of the cut-off bidder on the board; this price is called the MARKET PRICE. Each bidder who bids “above” the market price will be able to purchase one unit of the good at that price. Now pay attention to the record table on page 5, you will be asked to record the market price in the third row of the record table that corresponds to “MARKET PRICE.” After round 1 is finished, we will continue with rounds 2 and 3. Earnings: 31 Your earnings in US cents in each round will be rounded to the nearest quarter and will equal: = Your redemption value – the market price (if you obtain X) ……….OR = 0 (if you do not obtain X) Record your earnings in the last row of the Record Table. Exercise: To make sure you understand the auction rules, please fill in the gaps. Suppose that the computer generates a random number equal to 85 (remember that any number between 50 and 150 is equally likely). Suppose that your bid is 85, and that all players’ bids (including yours) are, in descending order, equal to: 142, 110, 87, 85, 70, 59, 55 and 0. Suppose the experimenter draws a ping pong ball with the number 5 written on it, the cut-off bidder is the 6th highest bidder, his/her bid is the market price and equals 59. 1. Do you obtain X? ________ 2. Does the player who submitted 59 obtain X? _______ 3. How much does each bidder who obtains X pay? _____ 4. Suppose that the participant who submits 142 has a value of 52, what are his/her earnings equal to? ______ 5. Suppose that the participant who submits 85 has a value of 150, what are his/her earnings equal to? ______. If she had submitted a bid of 85, what would her earnings be equal to? ______. 6. Suppose that the participant who submits a bid of 85 has a value of 50. What would her earnings be equal to? ______. Other questions… 7. You will learn about how many units are auctioned (before) or (after) choosing your bid. ______. 8. If the experimenter draws a ping-pong ball with the number 4 written on it, then the cutoff bidder’s bid is the ______ highest. 9. Suppose that the cut-off bidder’s bid is 61, the market price is _______. All those people whose bids are ________will get the units at a price of ________. Notice that you always make money if you can buy a unit at a price that is less than your redemption value, but you lose money if you buy a unit at a price that is more than your redemption value. Because only bidders who bid above the market price can obtain the item, you will always receive the unit for less than the amount you bid, so the most profitable strategy is to bid an amount equal to your redemption value. By bidding any amount less than your value, you only decrease the chance that you will make some money. Record Table – round 1 32 ID#: _______ Please fill in the cells. YOUR REDEMPTION VALUE YOUR BID MARKET PRICE YOUR EARNINGS FOR THE ROUND Earnings: Your earnings in US cents in each round will be rounded to the nearest quarter and will equal: = Your redemption value – the market price (if you obtain X) OR = 0 (if you do not obtain X) --------------------------------page break----------------------------Part 3: Mood Induction (Mood was induced in two of the three treatments by using the feedback and memory recall procedures – these procedures are available from the authors upon request) ID # _______________ Please answer the following questions: 1) Have you ever participated in an economic experiment? 2) Have you ever participated in an experiment other than economics? 3) Rate how you feel on the following scale by putting an X anywhere on the ruler below: Very happy/ in a very good mood Neutral Very unhappy/ in a very bad mood ------------------------page break------------------------Part 4: Decisions ID#: _________ Instructions: Your ID number is written in the upper-right side of this sheet. In this part you will participate in three rounds of an auction. Please pay close attention to the rules of the auction. Your earnings in this part will depend on your decision, the decision made by other participants and chance. You will be paid in cash at the end of the experiment. Auction Rules: 33 There will be three rounds of this auction. For all three rounds you will keep the same redemption value. In each round, we will auction a random number of units of a fictitious good that we will call good “X”. The number of units to auction will be determined by drawing one of eight numbered ping pong ball from this urn as described before. You will participate in the auction together with the 7 other participants. As before, your redemption value was determined using a random number generator. Any value between 50 and 150 was equally likely. All other participants also receive their own random redemption values. Since each person receives his/her own random redemption value, your redemption value will typically be different than those of other players. You will receive only one redemption value for the three rounds. How to bid: In each round you will bid for the unit “before” learning how many units are available in the auction; that is, before we draw the numbered ping-pong ball. Please pay attention to Record Table on page 13. You may submit a bid for one unit of X by filling out the second row of the second column that corresponds to “YOUR BID”. Once you have filled out your form, the experimenter will collect the record tables and all of the bids will be ordered from highest to lowest. Afterwards, you will be asked to write your bid for the next round. How to obtain a unit of X: After all participants submit their bids in all rounds, the experimenter will randomly choose the number of units to be auctioned each round by drawing the ping-pong balls three times with replacement. This will also determine the cut-off bidder and the market price for each round. Suppose that the first ball we draw has a number 2 written on it, the second has a number 3, and the third a number 4, then the cut-off bidder is the person whose bid ranks 3rd, 4th, and 5th for the first, second and third rounds, respectively. Each bidder who bids “above” the market price will be able to purchase one unit of the good at that price. However, you will not know whether you have bought the units until the end of the experiment. Once all decision parts in the experiment are finished, we will write down the market prices on your sheets and your payoffs before returning them back to you. Earnings: Your earnings in US cents in each round will be rounded to the nearest quarter and will equal: = Your redemption value – the market price (if you obtain X) ……….OR = 0 (if you do not obtain X) NOTE… In this part you will be paid for one of the rounds only! The round that counts towards your earnings will be determined randomly at the end of the experiment. You will not know, at the time that you make your bids, which auction will be the one that counts. All auctions have an equal chance of counting. -------------page break------------------------Part 5: Decisions ID#: _______ Instructions: 34 Your ID number is written in the upper-right side of this sheet. In this part you will participate in three rounds of an auction for a pair of movie tickets (i.e., two tickets). You may use the $15.00 that you were credited at the beginning of the experiment to make your bids. Please note that the $15.00 you were credited are yours and you should feel free to spend them or save them as you would any other money that you have. Please pay close attention to the rules of the auction. Your earnings in this part, which may or may not include the tickets, will depend on your decision, the decision made by other participants and chance. You will be given the tickets and paid in cash at the end of the experiment. Auction Rules: There will be three rounds of this auction. In each round, instead of bidding for a fictitious good, you will be bidding for a pair of movie tickets to Regal Cinemas. The rules of the auction will be similar to those in the previous auction. You will participate in the auction together with the 7 other participants. There will be 3 rounds of bidding in which a randomly selected number of pairs of movie tickets will be auctioned. Again, we will use the ping pong balls to determine the number of pairs of movie tickets to auction after you submit bids for all the three rounds. As in the previous part, only one of the auctions will count. At the end of today’s session, the experimenter will randomly determine the auction in which the movie tickets will actually be sold. You will not know, at the time that you make your bids, which auction will be the one that counts. All auctions have an equal chance of counting. This means that you can use as much of the 15 dollars in your account as you like in each auction without reducing the amount you have available to bid in other auctions. Since only one auction will count, you will receive a maximum of one pair of movie tickets (two tickets). How to bid: Please pay attention to Record Table attached to these instructions on page 17. You may submit a bid for a pair of Regal Cinema tickets by filling out the first row of the second column that corresponds to “YOUR BID”. Once you have filled out your form, you must turn it in to the experimenter. Afterwards, you will be asked to write your bid for the next round. How to obtain a pair of Regal Cinema Tickets: After all participants submit their bids in all rounds, the experimenter will randomly choose the number of units to be auctioned by drawing the ping-pong balls three times with replacement. All bidders bidding above the market price will receive a pair (two tickets) each and will pay the market price determined by the randomly selected cut-off bidder. We will write the market price in the third row of the record table that corresponds to “THE MARKET PRICE.” In this auction, you receive a pair of Regal Cinema tickets if you bid above the market price. Gains in product and dollars: Your earnings in US dollars in each round will be rounded to the nearest quarter. The individuals bidding at or below the market price in the auction will not receive the tickets, and no money will be deducted from their accounts. Thus, your gains equal: = A pair of Cinema tickets + $15.00 – the market price (if you obtain the tickets) OR = $15.00 (if you do not obtain the tickets) Record your earnings in the last row of your Record Table. 35