Running head: EFFECTIVENESS OF A SUMMER CAMP

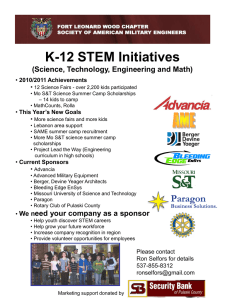

advertisement