WASC PREPARATORY REVIEW EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

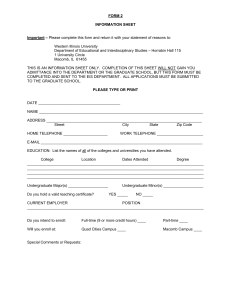

advertisement