Iran–The Chronicles of the Subsidy Reform Dominique Guillaume, Roman Zytek, and WP/11/167

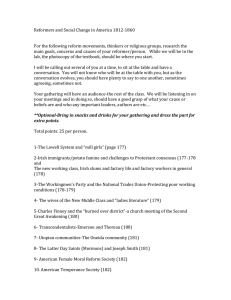

advertisement