LOOKING PAST THE ACTION: A STUDY OF THE EFFECTS OF STRUCTURE

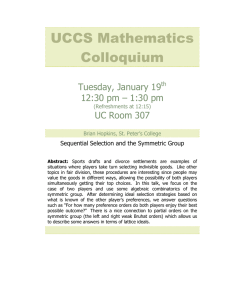

advertisement