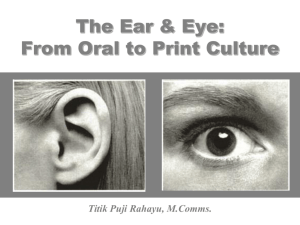

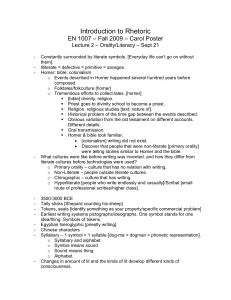

BEYOND ORALITY AND LITERACY: RECLAIMING THE SENSORIUM FOR COMPOSITION STUDIES A DISSERTATION

advertisement