THE STATUS OF INTERNATIONALIZATION IN U.S. COUNSELING PSYCHOLOGY DOCTORAL PROGRAMS A THESIS

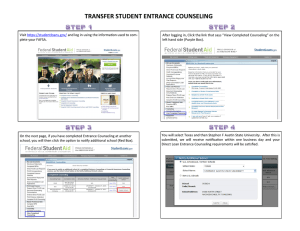

advertisement