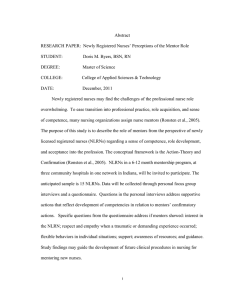

EVALUATION OF NEW GRADUATE NURSES’ PERCEPTIONS OF MENTORING A RESEARCH PAPER

advertisement