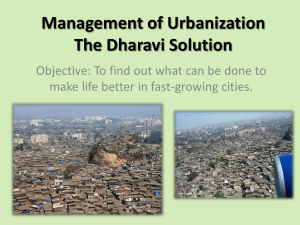

INTERVENTIONS IN URBAN INFORMALITY A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOL

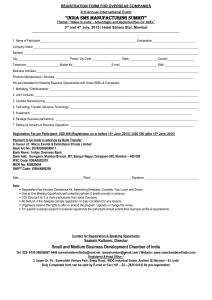

advertisement