Document 10943367

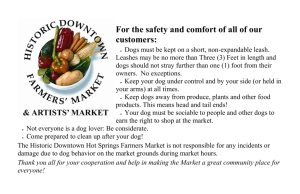

advertisement