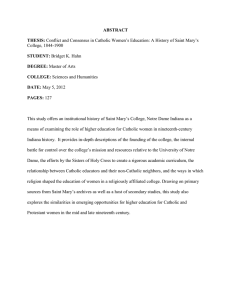

CONFLICT AND CONSENSUS IN CATHOLIC WOMEN’S EDUCATION: A A THESIS

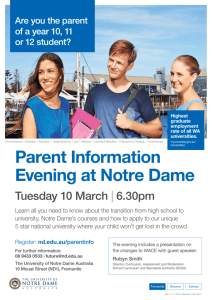

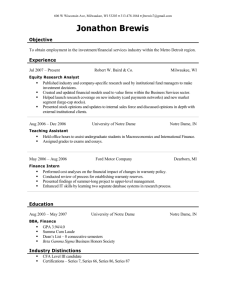

advertisement