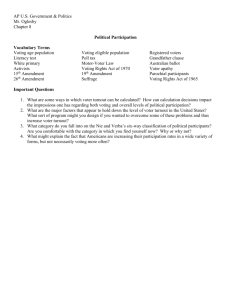

Political Knowledge and Voter Turnout A Thesis (THES 698)

advertisement