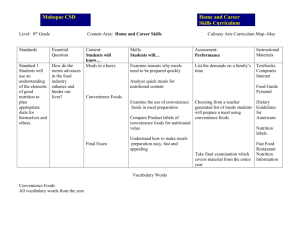

EMERGING FOOD PERCEPTIONS, PURCHASING, PREPARATION, AND

advertisement