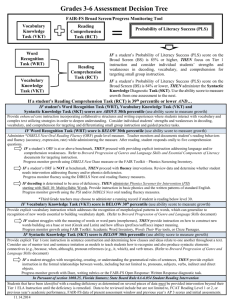

CAN ORAL READING FLUENCY SCORES ON DIBELS ORF PREDICT ISTEP RESULTS?

advertisement