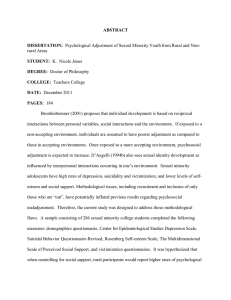

PSYCHOLOGICAL ADJUSTMENT OF SEXUAL MINORITY YOUTH FROM RURAL AND NON-RURAL AREAS

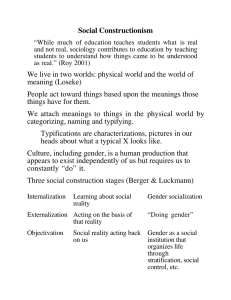

advertisement