Document 10927920

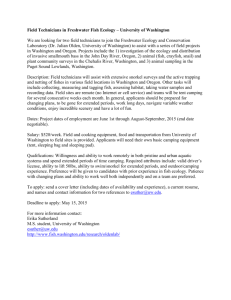

advertisement