A VETERANS TRANSITION SUPPORT PROGRAM A CREATIVE PROJECT

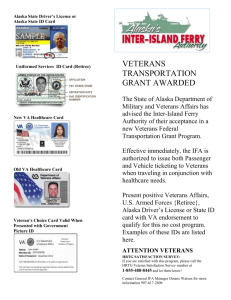

advertisement