G C :

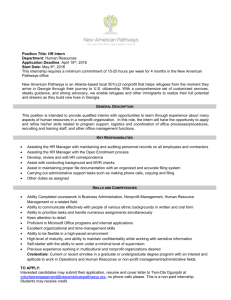

advertisement