Journal entry 1 Race and Serving at Beulah Soup Kitchen

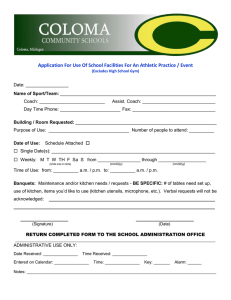

advertisement

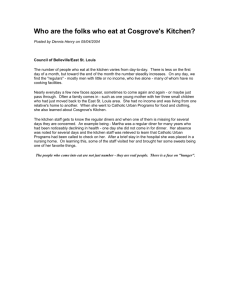

Race and Serving at Beulah Soup Kitchen Haydn Bates Honors Religion and Politics 2003 Journal entry 1 March 8, 2003 “This morning I went to the Beulah Baptist Church for the first time in order to help with the weekly Saturday soup kitchen. I arrived a bit early and caught the very end of the morning mass, at which point I realized that Beulah was a black church. Having come from a predominantly white town in Connecticut, I had never before in my life been to or even seen a black church. It was the first time in my life that I, if only for a few hours, was in the minority race. “At first, I felt a bit awkward, not sure of what to say or what to do. However, the realization soon washed over me that everyone at the kitchen, including myself, was united by an urge to help…. We had all answered a “call to service” regardless of the races or sexes to which we belonged. ‘We are bound to each other,’ wrote James Cone in Martin and Malcolm and America, ‘not just blacks with blacks and whites with whites…all races of people in the United States and throughout the world are one human family, made to live together in freedom’ (Cone 295). Such thoughts echoed through my head as I folded charity clothes for the kitchen visitors to take, and helped prepare the food for them to eat. I had my freedom, now I was helping others who hadn’t yet been able to achieve theirs. “Busy at work at the back of the kitchen, I soon heard people shuffling in the doors of the outer hall; off the cold, mean streets of Poughkeepsie into the warm, friendly atmosphere of the church. I watched as they sat down at the tables, filling the previously empty room. As I looked over the crowd I came to a stunning realization: nearly 85 percent of the room was made up of white people…I had expected mostly black people to visit the soup kitchen. George Gilder writes in Wealth and Poverty, ‘We have been willing to suppose that the poor were some alien tribe…It helped that many of the poor were black. They looked different; perhaps they were different’ (Gilder 64). The truth was before my eyes, though. The poverty‐stricken visitors to the soup kitchen were not at all alien or different‐looking; in fact, most of them looked like they could be my very own uncles or aunts or even my sisters or brothers. I had an epiphany that poverty was not simply a race issue; it wasn’t a plague that affected only people with darker pigmentation. It was an issue for everyone, and it was everyone’s responsibility to eliminate “My experience at the soup kitchen this morning was truly eye‐opening. Rather than whites helping to give clothes to and cook a meal for blacks (as I had expected), it was predominately blacks who were helping predominately whites. As I left the church I felt that I had learned an absolutely essential lesson….The races are united in suffering with poverty, and now the races must be united in the fight to end poverty. During the hours that I spent at the soup kitchen this morning, I felt like I was part of a great cause. There were no distinctions for race amongst the people working in the kitchen and there were no distinctions amongst those eating at the kitchen. We were united as human beings; united in the fight against poverty.” [Haydn revisits Beulah the next semester.] He writes: “As I walked through the door…it felt like I’d never left. Doris Brown was buzzing around like usual, preparing the room for yet another Saturday morning meal. I wanted to go up to her and say hello, but I was a bit afraid that she wouldn’t remember me. I spent a great deal of time here last semester, and the people made a lasting impression upon me, but I wasn’t sure if I’d made a lasting impression upon them. “Sheepishly, I trotted up along side Mrs. Brown, and managed to eek out a greeting. For me, talking to Doris is like talking to a movie star; I have so much respect for her that the intimidation factor practically paralyzes my body. So, you’ll understand, then, how floored I was when she responded with a giant smile and a jubilant, ‘Hello, Hayden!’ I nearly fell over. “Doris pointed to a newspaper clipping that was posted on the wall, and I noticed that there were a few identical postings elsewhere throughout the room. The clipping was of an article, written in The Poughkeepsie Journal, which praised a brief presentation I made at last spring’s Praxis Forum. The talk had dealt with my time at Beulah, and the many things I had learned while there….This just about knocked me out. Here I was, unsure if anyone would remember me, only to find out that I’d gained ‘celebrity status’ in my absence! My heart was warmed. I had made a difference, even if it was a minor one. “My objective…this morning was to interview Doris Brown in order to gain some insight into her life and work…..Doris agreed…and so we found a quiet place to sit down and talk….[She said that] despite long hours and hardships over the 21 years, she told me that her time has been well spent. “Doris has seen major transformations in Poughkeepsie during her time here, and they haven’t been positive ones…. ‘There was more of a mindset of community here in the 1960s,’ she said. ‘As income levels have decreased and poverty has emerged, people have become more self‐centered. People’s sense of values have changed…Its apathy going hand in hand with poverty.’ She looked at her grandchildren as she said this….I recalled what I had recently read in Greg Duncan’s Consequences of Growing Up Poor: ‘Children raised in poor families are more likely than affluent children to drop out of high school and to have a baby as a teenager. When poor children grow up, they get less education, are less likely to work, earn lower wages when they do, and are more likely to become single parents’ (Duncun 49). “There is a …quotation on our syllabus, ‘The ultimate test of America’s political and economic arrangements may be our willingness to raise the children of inner cities in “more healthy, more cherishing, more optimistic ways.”’ I read this to Doris and she solemnly nodded her head in agreement, as if she knew it was true, but doubted whether it was totally realistic. “But how do you go about rescuing these children….Doris told me that she believes that inner city areas, where poverty is at its worst, need to develop strong communities and positive social atmospheres, so that children may flourish within them. She has seen, firsthand, the building of community in the Beulah Baptist Church soup kitchen, a model prototype of what the Bush administration would like to see nationwide through its faith‐based initiatives. ‘Folks can come here and have someone to talk to,’ she said. ‘They get the chance to see old friends, and converse with them…Everyone who comes in here is on equal footing….’ “Doris has made a tremendous difference in so many lives through her love for community and dedication to public service. She is an intoxicating presence…. “One soup kitchen visitor summed up her effect: ‘She builds me up to send me back into the real world.’ Through talking to her, I am more convinced than ever that real change in the ghettos can only come through grassroots movements. If only we had a few more Dorises….