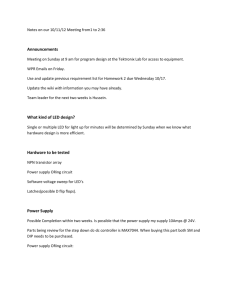

T A ?

advertisement