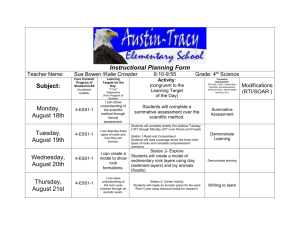

THE 1953 TO AT

advertisement