MAKING CONNECTIONS:

REDEVELOPING THE PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE NETWORK FOR

DOWNTOWN MUNCIE

A CREATIVE PROJECT

SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR THE DEGREE

MASTERS OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING

BY

NATHANIEL HUNTER, B.S.

DR. ERIC KELLY – ADVISOR

BALL STATE UNIVERISTY

MUNCIE, INDIANA

DECEMBER 2009

Initial Creative Project Proposal

Making connections: Redeveloping the Bicycle and Pedestrian Network for

Downtown Muncie

Muncie, Indiana like many other cities in the United States is working towards improving its original downtown. This creative project focuses on creating a functional Pedestrian and

Bicycle Network for Muncie’s Downtown with connections to the surrounding neighborhoods. The current network is disconnected, with facilities abruptly ending and barriers making it difficult for pedestrians and bicyclists to efficiently make their way to and from the downtown from surrounding neighborhoods. Also, the current condition of the

Downtown sidewalks and bicycle network are below average excluding the White River

Greenway. With this project an improved Bicycle Pedestrian Network is proposed.

This proposal looks at creating direct routes for pedestrians and bicyclists, eliminating barriers and completing facilities that will increase the connectivity of the Downtown to the surrounding neighborhoods. In doing so, this project will also look into the behavior of cyclists and pedestrians. The proposal will also evaluate the current network to identify areas in need of improvement to increase the quality of the network. New development and improvements to the network will also be prioritized to create the most direct and efficient routes first. Funding will also be investigated to determine if progression on the proposed

network can be made on a shorter time line.

The improved pedestrian bicycle network will not only improve the Downtown, but it will also benefit the city’s transportation, environment, energy, health, and economy.

Concerning transportation, 40 percent of all trips are less than two miles and can be made with a 10‐minute bike ride. Consequently cars could be removed from our congested roads.

One would also think about the improvement in air quality as 60 percent of the pollution created by automobiles is emitted during the first few minutes of operation while the vehicle’s engine warms up. Some might even consider the 30‐minute walk, an alternative to the 10‐minute bike ride with the same benefits. By improving the bicycle pedestrian network the city will also improve the quality of life. The number of people bicycling and walking the streets can be an indicator of a community’s livability, a factor in attracting businesses and workers. Communities with bicyclist and pedestrians allow for greater interaction of its citizens, which produces a greater sense of place and identity. Bicycling and walking also benefit citizens by improving their health and reducing obesity. A good bicycle and pedestrian network can also lower the need for an automobile and provide relief for those who cannot afford them.

ii

Table of Contents

Initial Creative Project Proposal......................................................................................................... ii

List of Figures...............................................................................................................................................v

INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1

LITERATURE REVIEW............................................................................................................................. 9

1. Early History of Muncie’s Pedestrian System .....................................................................9

2. Benefits of Walking and Biking................................................................................................9

A. Health ...........................................................................................................................................................10

B. Economic.....................................................................................................................................................13

C. Environment/Energy.............................................................................................................................14

D. Transportation .........................................................................................................................................15

E. Quality‐of‐life.............................................................................................................................................16

3. Bicycle/Pedestrian Environment and Behavior ............................................................. 16

A. Choosing to Cycle or Walk...................................................................................................................17

B. Choosing a Route .....................................................................................................................................18

4. How Far Pedestrians Are Willing to Walk or Cycle ........................................................ 19

5. Why People Walk....................................................................................................................... 20

6. Types of Pedestrians and Cyclists........................................................................................ 21

7. Walkability/ Bike Ability Audit ............................................................................................ 23

8. Creating the Network ............................................................................................................... 24

A. Barriers........................................................................................................................................................24

B. Design Standards.....................................................................................................................................25

C. Trip Generators – Destination Points .............................................................................................27

D. Safe Routes to School.............................................................................................................................28

E. Pedestrian Facilities ...............................................................................................................................28

F. Bicycle Facilities .......................................................................................................................................29

G. Complete Streets\Livable Communities .......................................................................................30

H. Local Ordinances.....................................................................................................................................30

I. Prioritizing Improvements ...................................................................................................................30

J. Sample Pedestrian and Bicycle Plans...............................................................................................32

9. Coordination Needed ............................................................................................................... 33

MUNCIE’S EXISTING PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE PLAN.......................................................34

DATA COLLECTION ................................................................................................................................46

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS ...................................................................................................................55

DOWNTOWN MUNCIE PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE PLAN...................................................65

I. Human Factors in Creating the Network...................................................................................66

1. Urban Design Factors.............................................................................................................................66

2. Route Choice ..............................................................................................................................................67

3. How Far Pedestrians Are Willing to Walk or Cycle...................................................................67

4. Why People Walk or Bicycle ...............................................................................................................69

iii

II. Goals.........................................................................................................................................................69

III. Downtown Recommendations ...................................................................................................71

IV. Recommended Downtown Paths...............................................................................................83

V. Design Standards................................................................................................................................95

1. Legal Requirements................................................................................................................................95

2. General Design Standards....................................................................................................................96

3. Pathway Standards .................................................................................................................................98

CONCLUSIONS...........................................................................................................................................99

Works Cited & References ................................................................................................................101

Appendix A: Abbreviations and Acronyms ...............................................................................105

Appendix B: Glossary..........................................................................................................................106

Appendix C: Community Connections Survey..........................................................................109

Appendix D: Community Connections Survey Results.........................................................116

iv

List of Figures

Figure 1: Map: Downtown Muncie Pedestrian and Bicycle Network Focus

Area……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1

Figure 2: Map of Muncie, Delaware County, Indiana……………….……………………….. 4

Figure 3: Population Time Line.....………………………………………………………………...... 5

Figure 4: Enrollment Statistics for Ball State University..………………………………… 5

Figure 5: Age Distributions Graphs, City of Muncie, Delaware County, and

Indiana………..................................................................................................................... 6

Figure 6: Age Distribution Percentages, City of Muncie, Delaware County,

Indiana.……………………………………………………………………………………….…. 7

Figure 7: Physical Activity Benefits……………..…………………………………………………. 11

Figure 8: Health Risks Linked with Obesity....………………………………………………..... 12

Figure 9: Common Environmental Factors….………………………………………………….. 17

Figure 10: NHTS, 2001 Trip Purposes Results.………………………………………………….. 21

Figure 11: Omnibus Survey, 2003 Trip Purpose……………………………………………….. 21

Figure 12: Type of Pedestrians……………………..………………………………………………….. 22

Figure 13: Type of Bicyclists………………………...………………………………………………….. 22

Figure 14: Common Barriers………………………..………………………………………………….. 25

Figure 15: Bicycle Hazards…………………………..…………………………………………………... 25

Figure 16: Considerations for Pedestrian Facilities.………………………………………….. 29

Figure 17: AASHTO’s Variables for Priority in Retrofitting.……………………………….. 32

Figure 18: Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan Classification Variables for

Sidewalk Projects Priority………………………………………...…………………….. 35

Figure 19: List of Project Priorities for Figures 10 & 11…………………………………….. 38

Figure 20: Map: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Proposed

Routes……………………..………………………………………………………………...…… 39

Figure 21: Map: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Project

Priority…………………………………………………………………………………………... 40

Figure 22: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Project Priority

Costs……………………….……………………………………………………………………… 41

Figure 23: Map: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan:

Pedestrian/Bicycle and Roadway Coordination Project..…………………... 43

Figure 24: Map: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan:

Pedestrian/Bicycle Network Water Crossings………………………………….. 44

Figure 25: Map: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan:

Sidewalk Priority Areas…………………………………………………………………... 45

Figure 26: Delaware County Geospatial Resources’ GIS Data.…………………………….. 47

Figure 27: 2009 Sidewalk Survey………………….…………………………………………………. 49

Figure 28: Sidewalk Condition Excellent…………………………………………………………... 50

Figure 29: Sidewalk Condition Good….……………………………………………………………... 50

Figure 30: Sidewalk Condition Fair………………………………………………………………….. 51

Figure 31: Sidewalk Condition Poor..…………………………………………………………… 51

v

Figure 32: Sidewalk Condition None.……………………………………………………………….. 52

Figure 33: Map: 2009 Sidewalks Surveyed………………………………………….

...

………….. 54

Figure 34: Sidewalk Segment Conditions...……………………………………………………….. 56

Figure 35: City Block Sidewalk Conditions...……………………………………………………... 56

Figure 36: Curb Ramp Counts………………...………………………………………………………... 57

Figure 37: Pedestrian Barriers and Hazards Count.…………………………………………... 58

Figure 38: Map: Detailed Sidewalk Conditions...………………………………………………... 61

Figure 39: Map: Generalized Sidewalk Conditions...………………………………………….. 62

Figure 40: Map: Points of Conflict…………………...……………………………………………….. 63

Downtown Muncie Pedestrian & Bicycle Plan Figures

Figure 1A: Map: Downtown Muncie Pedestrian and Bicycle Network Focus

Area……………………………………………………………………………………………...... 66

Figure 2A: Map: Downtown Muncie Population Density…...…………………….....……… 68

Figure 3A: Typical Pedestrian and Bicycle Plan Goals.……………………………………….. 70

Figure 4A: Downtown Muncie Pedestrian and Bicycle Network Focus Area.…........ 74

Figure 5A: Problem Curb Ramps………………..…………………………………………………….. 76

Figure 6A: Sidewalks Replacement….……...……………………………………………………….. 78

Figure 7A: Downtown Routes…………………………………………………………...…….…......... 84

Figure 8A: County Wide Proposed Routes………………………………………………...……… 85

vi

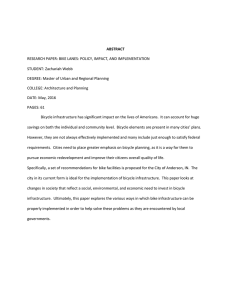

INTRODUCTION

Muncie, Indiana like many other cities in the United States is working toward improving its historic downtown. This creative project focus on creating a functional

Pedestrian and Bicycle Network for Muncie’s Downtown with connections to the surrounding neighborhoods. The current network is disconnected, with facilities abruptly ending and barriers making it difficult for pedestrians and bicyclists to

Focus Area

Figure 1‐Downtown Muncie Pedestrian and Bicycle Network

Focus Area

efficiently make their way to and from the downtown from surrounding neighborhoods. Also, the current condition of the Downtown sidewalks and bicycle network are below average, excluding the White River Greenway that runs through the Downtown. With this project an improvement to the pedestrian and bicycle network will be proposed.

This creative project also looks at creating direct routes for pedestrians and bicyclists, eliminating barriers and completing facilities that will increase the connectivity of the Downtown to the surrounding neighborhoods. In doing so, this project also looks into the behavior of cyclists and pedestrians. The proposal will also evaluate the current network to identify areas in need of improvement to increase the quality of the network. New developments and improvements to the network will also be prioritized to create the most direct and efficient routes first.

A good plan in many cases can become complex and create the need to be extremely comprehensive which is difficult. At many points when working through this project, it was found that additional information was needed continually adding to the project. The subject matter covered in this comprehensive pedestrian and bicycle plan not only address pedestrian/bicycle variables, but the unique demographics of Muncie. This small Downtown Muncie project was not intended comprehensively cover all the materials in a pedestrian/bicycle plan but to create a

starting point for future city wide plan.

2

Pedestrian/Bicycle Plan Variables:

•

Pedestrian/Bicyclist Behavior

•

Willingness to Walk/Bike

•

Type of Pedestrian

•

Type of Bicyclist

•

Walkability and types of Audits

•

Barriers and Hazards

•

Trip Generators

•

Pedestrian Facilities

•

Bicycle Facilities

•

Complete Streets

•

Prioritizing Construction and Improvements

•

Ordinance

When considering this project, Muncie has many unique demographics to consider. The city of Muncie is located in East Central Indiana as shown in Figure

2.The city of Muncie is centrally located in Delaware County and is the county seat.

Muncie is currently the eighth (8th) largest city in Indiana. In 2006, the population was estimated to be at 61,683, which is 15,533 less than its peak population in 1980 shown in Figure 2 (page 4). Data shows that the student population of Ball State

University has risen from an average of 19,000 students in the 1990s to an average of 20,000 in the 2000s. The population curve is a little unusual as a large portion of the population falls in the 5‐19 age group and the second largest range falls in the

20‐24 age group. This latter population can be account for by the large student population at Ball State University. Figures showing the Ball State University student enrollment and the population charts are shown on pages 5‐7.

3

Delaware County and the City of Muncie

Located in the State of Indiana

Figure 2‐ Map of Muncie, Delaware County, Indiana

4

Figure 3‐Population Time Line. Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census

Figure 4: Enrollment Statistics for Ball State University

5

Figure 5‐Age Distributions Graphs, Muncie, Delaware County, and Indiana

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census

6

=3-6>4(+,?

large age group with a slightly higher percentage is the 20-24 range. Th of students at Ball State University.

!"#$%&'(()'*#&'+",-%".$-"/0'1&%2&0-3#&,'4/%'5$02"&6'+&7383%&'9/$0-:6'30;'-<&'=-3-&'/4'>0;"3036'

2/?@3%"0#'(AAA'B'(AACD''=/$%2&E'FD=D'G$%&3$'/4'-<&'9&0,$,D

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census

Ethnicity and Race

Th

The goal of providing an improved pedestrian bicycle network will not only improve the Downtown, but it will also have effects benefiting transportation, the environment, energy, health, and economy. Concerning transportation, 40 percent grants. Muncie’s population is generally composed of White (Caucasian American), Black (African of all trips are less than two miles and can be made with a 10‐minute bike ride.

Think of all the cars that could be removed from our congested roads. One would also think about the improvement in air quality as 60% of the pollution created by fi c

Th Th

African Americans within the Muncie community. Populations of people of 2 or more races, people of the Hispanic race and people of the Asian races are the next highest minorities. A detailed table of

Muncie’s racial demographics and its recent changes is provided on the following page.

automobiles is emitted during the first few minutes of operation while the vehicle’s

Household information is bene fi cial when analyzing population data. In the following tables you will engine warms up. Some might even consider the 30‐minute walk, alternative to the to decrease. For example, a city with 5 houses once had a population of 16 people, but now has a

10‐minute bike ride with the same benefits. By improving the bicycle pedestrian only has 220. Th network the city will also improve the quality of life. The number of people bicycling and walking the streets can be an indicator of a community’s livability, which has an impact on attracting businesses and workers. Communities with bicyclists and pedestrians allow for greater interaction among its citizens, which produce a

#$%&'()'*+,-$./0'12&.34'53460'7'8.-4.3%$(,'*30%.4'593,'2':;;< greater sense of place and identity. Bicycling and walking also benefit by creating

!"

7

an area for activity for cities to improve their citizen’s health and reduce obesity. A good bicycle and pedestrian network can also lower the need for an automobile and provide relief for those who cannot afford them.

8

LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Early History of Muncie’s Pedestrian System

Muncie has an interesting past. Muncie was a quiet town but erupted into a bustling city. The boom began in the mid 1800s with the appearance of the railroad and again with the discovery of natural gas in Central Indiana in the 1880s. Muncie became one of the fastest growing cities in the country, and with that growth the city made great investments in its transportation system. In 1882 there were only

15 miles of streets and no paved sidewalks, but by 1891 Muncie had five (5) miles of sandstone walk, five (5) miles of brick walk, and two (2) miles of cement walk

(General W. H. Kemper 1907). Muncie had high standards for its infrastructure in

1888 as the city council stated that all walks should be of sawed sandstone, six feet wide, the gutters of dressed limestone slabs, while grass should be grown between the walk and curb. A few years later in 1890 when cement became popular the council forbade the use of a “new fashioned” concrete walk on East Jackson and ordered the city engineer to make it of brick (General W. H. Kemper 1907).

2. Benefits of Walking and Biking

A pedestrian/bicycle network can create many benefits and can completely justify their costs, paying for themselves. Sense of place, health benefits, economic,

transportation, and many others are persuasive factors to anyone with a hint of interest in creating a strong and useful pedestrian/bicycle network. Continuous publication of the positive impacts of pedestrian/bicycle network will help to further reinforce the requirements for this mode of transportation.

A. Health

Walking or bicycling plays an integral role in enhancing physical and mental health by providing physical exercise as well as relaxation opportunities. Walking and bicycling also provide a venue for social interaction and space for recreational activities. Overall, an increase in pedestrian/bicycle trips creates a healthier and

more active livable community.

In 2001, the National Household Travel Survey found that roughly 40 percent of all trips taken by car are less than 2 miles. This could be a short 10‐ minute bike ride for an experienced cyclist (type A bicyclists) or a 30‐minute walk. .

Pedestrian and Bicycle networks can play a large role in improving the health of a

city. On the following page are just a few of the benefits from participating in regular physical activity.

10

Physical Activity Benefits

Maintain Weight

Reduces blood pressure

Reduces risk for type II diabetes, heart attack, stroke, several forms of cancer

Relieves arthritis pain

Reduces risk for osteoporosis

Prevent and reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety

Boosts good cholesterol

Lengthens lifespan

Relieves back pain

Strengthens muscles, bones, and joints

Can improve sleep

Elevates overall mood and sense of well-being

Figure 7‐Physical Activity Benefits

Source: Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2009 and Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality 2009

Citizens who do not participate in regular exercise risk becoming overweight, or even obese. The rate of obesity has become a large concern in the United States with 49 of 50 states reporting an obesity rate of 20 percent or more. The Center for

Disease Control and Prevention also reported that 30 states had an obesity rate of

25 percent or greater and Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee were equal or greater than 30 percent. The rate of obesity in Indiana for 2008 was 26.3 percent.

The rate of obesity is of concern because of its negative health implications such as heart disease, hypertension, and Type II Diabetes. The following table is a more complete account for associated health conditions.

11

Health risks linked with obesity

Coronary heart disease

Type 2 diabetes

Cancer (endometrial, breast, and colon)

Hypertention (high blood pressure)

Osteoarthritis (a degeneration of cartilage and its underlying bone within a joint)

Dyslipidemia (for example, high total cholesterol or high levels of triglycerides)

Stroke

Liver and Gallbladder disease

Sleep apnea and respiratory problems

Gynecological problems (abnormal menses, infertility)

Figure 8‐Health Risks Linked with Obesity

Source: (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2009) and (Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality 2009)

The health conditions linked to obesity also generate large costs for the taxpayer in the form of health care. In 1998 it was estimated that taxpayers paid between 13.5 and 24.5 million dollars for Medicaid and Medicare expenses caused from obesity, and 24.6 to 27.6 million if one adds the medical expenses for those overweight(Finkelstein 2003). Finkelstein also reported thst if you add out‐of‐ pocket costs, private insurance, Medicare and Medicaid, costs totaled between 51.5

and 78.5 million dollars for medical expenses related to overweight and obesity.

Giving citizens access to a pedestrian/bicycle network allows many the opportunities to increase their levels of activity, lower their chances of becoming overweight, and consequently lower health care expenses and related taxes. This is important as popularity for a national healthcare plan increases.

12

Bicycling and walking not only offer an opportunity to improve physical health among citizens, but may also decrease obesity and monetary expences dedicated to related healthcare needs.

B. Economic

Bicycling and walking are affordable forms of transportation. The costs of operating a bicycle are about $120 a year, which includes the maintenance of the bike and the replacement of worn tires (The League of American Bicyclists n.d.).

Operating the typical car on the other hand costs $8,000, a sum accounting for 19 percent of a typical household income in 2004 according to AAA. Bicycling can also help to reduce health care costs as discussed earlier.

In addition to reducing transportation costs for average citizens, bicycling may also provide opportunities to create revenue. Organized groups, charities, and others have organized bicycling events such as races, or celebrations that can bring money into the local economy. In Lawrence, Kansas, a yearly bicycle event recently added a bike race to its agenda. This race is expected to attract 900 riders alone.

The city is donating some funds plus city services for the event. With the small investment the city is looking at gaining $600,000 in spending from participants and fans(Lawhorn 2009). Augusta, Georgia has also seen the benefits from bicycle events. In the 2006 Tour de Georgia part of the race ran through Augusta. It was estimated to have brought in $250,000 to the community and $32.6 million to the state of Georgia (Lombardo 2006).

13

Bicycle‐related economic activity can also generate money to the state economy. Wisconsin and Colorado, states with large scale manufacturing of bicycles and bike accessories, generate millions of dollars in activities and thousands of jobs.

Colorado bicycle‐related business has shown a contribution of over $1 billion to the state economy in annual activity (Alta Planning and Design 2006).

Bicycling and walking do not only bring in money to the economy; they also help to reduce government spending. With more bicycle and pedestrian trips there are fewer vehicle trips to cause wear and tear on the road. With fewer vehicles on the road, fewer accidents and less property damage can also be anticipated. A decrease in vehicles also decreases the demand for additional roads, lanes and parking. Reducing the vehicle trips and increasing bicycle and pedestrian trips can be a win, win in regards to economic benefits.

C. Environment/Energy

When citizens get out of their vehicles and walk or get onto their bicycles they are eliminating pollutants they would have created in fuel emissions by taking a vehicle. According to the League of American Bicyclists, bicycles currently displace over 238 million gallons of gasoline per year, by replacing car trips with bicycle trips. Not only did those who bicycle save gasoline, but they are also helping to reduce congestion by not having their vehicle on the road, eliminating the emissions caused by idling in the congestion. By eliminating pollutants caused by congestion, less contaminates end up in the air and on roadways which flows off the streets end up in our lakes and rivers.

Walking and bicycle trails that help make up the bicycle

14

and pedestrian network also provide environmental benefits. Trails help to protect plants and animals, create buffers for lakes and rivers, and filter pollution from agriculture and road runoff, along with other benefits. The plants along the trails create oxygen and filter air pollution, such as ozone, sulfur dioxide, and carbon dioxide. Additionally, these alternative transportation methods do not contribute to the noise level as cars often do reducing noise pollution.

D. Transportation

Briefly mentioned before, in 2001 the National Household Travel Survey

(NHTS) found that roughly 40 percent of all trips taken by car are less than 2 miles in length, the equivalent of a short bike ride or a 30 minute walk. Many people already chose to leave their vehicles at home, making their trip on foot or bicycle.

Bicyclists alone make nine million trips a day or 3,285,000,000 trip per year, in the

U.S. (2001 NHTS). Those citizens that chose to walk or ride a bike reduce local traffic and congestion. Otherwise, congestion reduces mobility, increases auto‐operating costs, adds to air pollution, and causes stress.

Additionally, there are many who cannot drive or have the luxury of owning a vehicle. According to the NHTS, one in 12 U.S. households do not own an automobile and approximately 12 percent of persons 15 or older do not drive.

Those that cannot drive such as the poor, young and elderly can benefit greatly with the development of a bicycle and pedestrian network.

15

E. Quality‐of‐life

Realtors, homebuyers, and others have associated the numbers of those who walk and bicycle as an indicator for an area’s quality‐of‐life. An active pedestrian/bicycle path is now perceived as giving a sense of community, which is attractive to businesses and their employees. Bicycle and pedestrian networks create an additional location for neighbors and other citizens to interact and create or strengthen relationships. The bicycle and pedestrian network increase one’s quality‐of‐life by improving the time spent traveling.

3. Bicycle/Pedestrian Environment and Behavior

To date there is little research that has evaluated the relationship between the factors of the physical environment and the bicyclist/pedestrian. This may be due to the fact that pedestrian and cyclist behavior is highly complex and difficult to study. Many reports and articles found in this study have name factors in the environment that affect a pedestrian’s behavior, but very few concrete connections have actually been made. The studies that do look at the bicycle/pedestrian environment often study why those are choosing to walk or cycle instead of using their auto(Schlossberg, et al. 2007)(B. E. Saelens, et al. 2003).

16

Common Environmental Factors

Aesthetics

Bicycle and Pedestrian Facilities

Connectivity

Mixed Land Use

Residential Density

Walking/Cycling facilities

Traffic Safety

Crime Safety

Traffic

Traffic Block pattern and length

Figure 9‐Common Environmental Factors

A. Choosing to Cycle or Walk

Current studies on how environmental factors affect the behavior of cyclists and pedestrians are limited(B. E. Saelens, et al. 2003).

Many studies have found that bicycle and pedestrian trips have a strong positively correlate with density (Saelens,

Sallis and Frank 2003). There are also strong positive correlations between connectivity and land use i . Urban design, such as, short block length and a gridded street pattern also seem to have positive effect on bicycle and pedestrian trips, but the relationships are not as strong. Additionally, aesthetic factors have been found to increase physical activity behavior(Humpel, Owan and Leslie 2002). Bicycle and pedestrian facilities have indications of a positive correlation with bicycle and pedestrian trips, but there are limited studies and data available making this correlation unreliable(Saelens, Sallis and Frank 2003). Areas that need further study are: bicycle and pedestrian facilities, traffic calming, and crime.

i

A mixed land use had a strong correlation with pedestrian and bicycle trip, but the relationships became even stronger when nonresidential uses, such as, shopping and employment, were in close proximity to residential uses.

17

B. Choosing a Route

Statistically, pedestrian/bicyclists have been show to use several factors when determining a route. The view of a route, travel speed of nearby vehicles, perceived safety, and directness are items one may consider before or while on a trip. A study by Mineta Transportation Institute found that the most significant factor in choosing a route is efficiency, followed by traffic safety, and than aesthetics.

In most cases, cyclists and pedestrians prefer to take the most direct and convenient route, indicating the importance placed on time. The second priority of pedestrians was traffic safety. Pedestrians find comfort in having traffic calming devices present and in traffic that follows a safe driving speed(Schlossberg, et al. 2007). Following in importance as indicated by travelers is the condition of the facilities, such as the sidewalk. Lastly, pedestrians look for pleasant aesthetics such as landscaping when considering their choice in routes. These results are from a single study and should not be considered conclusive at this point, as the study has not yet been duplicated with a more diverse sample.

Information from this study is still useful, as the author has found no other studies that provide this type of data. The results were not surprising and have supported implications that have been made articles over the years. It is not a far stretch to assume that people value their time. We can now say with some perspective that when creating a bicycle or pedestrian network planners should prioritize with efficiency, traffic safety, facility condition, and aesthetics.

18

4. How Far Pedestrians Are Willing to Walk or Cycle

Some authors claim that most pedestrians are only willing to walk an average of ¼ mile; however the methods in these studies are faulty and the data is unreliable. It was not the fault of those conducting the study; it has been found that half of participants cannot accurately estimate the distances they travel. In the

Mineta Transportation Institute, researchers found that participants were off by 45 percent on thier estimated trip distance. This error in distance was found in a survey where participants were asked to estimate their trip distance and then trace their route on a printed map. On average, the guesses erred by 0.20 miles.

The Mineta Transportation Institute findings also indicated pedestrians walk farther than previously thought, at least when walking to a transit center. The study found that people on average, were walking 0.47 miles, almost twice the distance originally reported. This new finding deserves attention as it could affect urban planning in multiple areas such as Transit Oriented Developments (TODs). This, of course, will need further study with the mapping survey technique used in this study.

For bicyclists, determining how far one will ride can vary greatly based on the cyclist community in the area. Many cyclists ride for recreation, for sport or to commute and can cover a large distance on each trip. When considering multiple factors, time is still one of the most significant issues implicating how far one will travel. Time can determine how long a trip can be, based on one’s athletic ability, or be a value for comparison when considering other forms of transit. If there are

19

greater facilities with few barriers, a bicyclist can cover a longer distance in a shorter time than when the bicyclists must travel with poor facilities with barriers. .

Another issue is how well an individual is accustomed to riding. An individual who rides everyday will have few problem riding, but others may become sore and fatigued from the same experience (Forester 1994). In other works, soreness and fatigue can be limiting factors. Little data was found concerning bicyclists as a whole, the data that was found was old and focused in on small segment of cyclists making it difficult to make a generalization for all bicyclists. A better measurement in future research may consider time versus distance for a more generalized measure that would cover all type of cyclists in various conditions.

5. Why People Walk

Individuals walk, run, or jog for many reasons including heath, exercise, and work. Two recent surveys studied the purpose of one’s pedestrian trip, one by the

Federal Highway Administration and the other by the Bureau of Transportation

Statistics. The Federal Highway Administration used their 2001 National Household

Travel Survey (NHTS), formerly the Nationalwide Personal Transportation Survey

(NPTS), to determine the purposes of walking trips. The Bureau of Transportation

Statistics contracted Omnibus to conduct their survey. The two surveys although similar, are stated differently and have differently named categories, which created results. The results for the two surveys are found on the following page.

20

NHTS: Trip Purposes as Percentage of Walking compared to Other

Modes, 2001

Social and Recreational

Personal Family Business

School or Church

Percentage of

Walking Trips

44.7

36

11

Percentage of

Other Modes

26.6

43.8

9.8

To/From Work or other Work/Business related

Other

6.6

1.5

18.8

0.8

Figure 10‐ NHTS, 2001 Trip Purposes Results

Omnibus Survey, 2003 Asked all respondents for what purpose they walk, run, or jog:

Purpose

Percentage

(weighted)

Commuting to work or school

Recreation

Exercise/for my health

Personal errands (to the store, post office, walking the dog, and so on)

6.18

10.3

60.35

Required for my job

19.42

3.75

Figure 11‐Omnibus Survey, 2003 Trip Purpose

6. Types of Pedestrians and Cyclists

Pedestrians are diverse, making them difficult to plan for comprehensively.

There are walker and joggers, people who enjoy a stroll, parents who walk with children, people with pets, elderly, and individuals with disabilities, all who have different needs when developing a pedestrian system. However, facilities should be

created to meet the needs of all users.

21

Types of Pedestrians

Ambulatory Impaired

Cognitive Impaired

Dog Guided

Elderly

Hearing Impaired

Joggers

Parents and Children

People with Pets

Prosthesis

Scooters

Walkers

Waling Aid Users

White Cane Users

Wheelchairs

Figure 12‐Types of Pedestrians

Cyclists are also a diverse group with large variation in experience and skills.

With this group there are recreation riders, commuters, children, novice riders, and others, all who have their own needs and levels of comfort. Cyclists are now commonly divided up into three different groups of cyclists: advanced, intermediate, and beginner.

Types of Bicyclists

Type Description

A

B

C

Advanced

Intermediate

Novice

Figure 13‐Type of Bicyclists

Type A ‐ Advanced Bicyclists

Advanced Bicyclists are the most skilled of the three types of cyclists.

Advanced cyclists will ride in almost any weather, are comfortable riding with traffic, and are able to ride at a continuous speed of 12 mph or higher. They also look for the fastest route, even if that means riding in heavy traffic. Types of riders

22

commonly found in this group are daily commuters, racers and tri‐athletes, bicycle messengers, and other athletically trained cyclists(Lydon 2008).

Type B‐ Intermediate Bicyclists

Intermediate Bicyclists are well skilled bicyclists with varying levels of experience. This type of rider is less comfortable riding with traffic, tends to take a longer route if it appears safer, and is unlikely to bicycle in unfavorable weather.

Type B riders also have lower distance and inconvenience thresholds then Type A cyclists. Type B cyclists will ride more when the proper bicycle facilities or streets with light traffic are present.

Type C‐ Novice Bicyclists

Novice Bicyclists have basic cycling skills. Type C riders are usually children and first‐time bicyclists. This group of riders prefer the sidewalk, recreational paths, and parks. You will usually only see this type of cyclist in pleasant weather.

7. Walkability/ Bike Ability Audit

When evaluating an existing pedestrian or bicycle system there are many ways to go about it. Some may wish to simply evaluate the sidewalk and its conditions. Others may need a comprehensive evaluation that surveys the entire environment of the pedestrian or bicyclist. In any case there are many surveys or audits to choose from. The Walkability Checklist and Bikeability Checklist are simple surveys created by the Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center that are great in targeting problem areas or collecting the basic data for a project. Systematic

23

Pedestrian and Cycling Environmental Scan (SPACES) and Pedestrian Environment

Data Scan (PEDS) are more complex surveys that collect a comprehensive set of valuable pedestrian and environment data.

8. Creating the Network

A. Barriers

For pedestrians and bicyclists it is important that they have a direct or efficient route for their trip, but often there are barriers in the way that slow or force the pedestrian/bicyclist to take a different route. It is important to remove these barriers because pedestrian and bicycle trips are often limited by the distance that the person is willing to travel or by the perceived distance of travel. If barriers can be removed it is possible to increase the number of pedestrian and bicycle trips.

(Institute of Transportation Engineers 1999)

Rivers, interstates, railroad tracks, and unsafe environments are all barriers quickly thought of, but there are many others that can be forgotten by those whom have chosen another primary mode of transportation. Wide roads, rough railroad crossings, inadequate bike lanes, lack of pedestrian and bicycle connections, signals not activated by bicycles, and poor, incomplete, or non‐existing facilities are all barriers that must be considered. Those who have chosen to walk or bicycle in a given area can assist in naming many more of the locally found barriers.

For bicyclists, hazards also can be considered a barrier. Street grates, debris, rough pavement, high traffic speeds, high traffic volumes, rumble strips, and others can be dangerous obstacles for those determined to make the bicycle trip.

24

Common Barriers

Rivers, creeks, canals

Railroad yard or tracks

Interstates, highways, county roads

Poor, incomplete, or non-exixsting facilities (sidewalks, paths, bike lanes)

High volume roads

Bridges

Wide Roads

Rough railroad crossings (more so on angled crossings)

Inadequate bike line (to narrow)

Lack of bicycle and pedestrian connections (where it would be suitable between residential areas and schools or shopping areas)

Unsafe Environments (crime and traffic safety)

Signals that are not activated by bicycle

Signals that cannot be activated by pedestrians

Figure 14‐Common Carriers

B. Design Standards

Bicycle Hazards

Street Grates

Debris

Rough Pavement

High Speed Limits

High Volumes

Rumble Strips

Narrow Traffic Lanes

Gravel Shoulder

Excessive Driveways

Figure 15‐Bicycle Hazards

When working with or creating new design standards for pedestrian and bicycle networks, experience in the area of laws and regulations becomes very helpful. A quick search of current standards will bring up Americans with

Disabilities Act (ADA) standards, American Association of State and Highway

Transportation Officials (AASHTO) guidelines, Federal Highway Administration

(FHWA) guidelines, Victorian Transportation Police Institute (VTPI) best practices, and many others. When working on the pedestrian plan specifically, the ADA legal

25

requirements must be met in order to avoid discriminating against those with disabilities. Initial improvements to facilities concerning design standards and an implementation timeline should have been addressed in a citywide transition plan to address these requirements. There are exemptions, deferments, and other reasons cities have not yet met requirements of the ADA. Careful review should be conducted to ensure that all requirements and standards are being met. Note that the ADA’s Revised Draft Guidelines for Accessible Public RightsofWay have not yet been approved and accepted into law, but there are standards from other sections of the act that are considered the minimum standard. Most importantly, the main purpose of the act is to eliminate discrimination and should be used as the primary

consideration in creating design standards.

~United States Access Board~

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1991 is a civil rights statute that prohibits discrimination against people who have disabilities. ADA implementing regulations for Title II prohibit discrimination in the provision of services, programs, and activities by state and local governments. Under the ADA, designing and constructing facilities that are not usable by people who have disabilities constitutes discrimination. In addition, failure to make the benefits of government programs, activities, and services available to people who have disabilities because existing facilities are inaccessible is also discrimination.

As of June 30, 2009, the ADA standards for the Public RightsofWay were still in a Draft form and not yet approved. The ADA standards issued by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Department of Transportation (DOT) were initially created in

1991 based on the original 1991 Americans with Disability Act Accessibility

26

Guidelines (ADAAG), which still set the minimum requirements. In the ADAAG there are section currently reserved for standards, such as the standards for the Public

Rights‐of‐Way, which are waiting to be created and approved. The ADA Standards for the Public RightsofWay currently needs the DOT’s and the DOJ’s approval before it is added to the ADAAG.

C. Trip Generators – Destination Points

Trip generators are important in informing the creation of a pedestrian/bicycle network. In determining or assigning trip generation points, several methods can be used based on need. To better design or create a pedestrian and bicycle network a planner needs to determine points of origins and destinations. The planner can then use skill and judgment based on knowledge and experience to determine demand for pedestrian facilities. This process is known as the intuitive or sketch planning approach and this process can be accomplished with greater precision by using a GIS system. The forecasting and modeling approaches are those similar to vehicle traffic demand methods and use some of the same theories(Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center n.d.). There is also new computer modeling that can better make predictions, but this method may over‐ complicate this process for smaller communities and is not typically cost effective

(Litman, et al. 2009).

There are many forecasting methods that can be used. The Federal Highway

Administration has reported on several models to allow municipalities to find a method that best meets their needs. The Guidebook on Methods to Estimate Non

27

Motorized Travel report looks at nineteen (19) different methods and is a great review of the available models.

D. Safe Routes to School

The Safe Routes to School program was created in 2006 and is managed by

National Center for Safe Routes to School. The purpose of the center and its program enable and encourage children to safely walk and bike to school. Through the center information is provided on multiple aspects used to create Safe Routes to

School (SRTS). With this program a community can come together and create a map of safe routes, create a school zone, place street crossings, add traffic calming, develop walking events, create a bicycle rodeo, add street signs to warn drivers, and provide information for crossing guards.

E. Pedestrian Facilities

When discussing pedestrian facilities there are many other considerations, such as the pedestrian environment, that must be made after meeting the ADA standards and additional design standards found appropriate by the transportation planners. When developing standards for facilities several design considerations can create a delight able environment found with Complete Streets. Additional considerations for pedestrian facilities the importance of it all should be in creating and attractive and inviting area that can be freely used by pedestrians. A great source for detailed information can be found at Walkinginfo.org.

28

Considerations for Pedestrian Facilities

Street lighting

Landscaping heighth

Clear visibility

Shade trees

Separation from vehicular traffic

Direct and continuous facilities

Traffic Calming

Considerations for shared walkways

Buffer type between pedestrian and vehicular traffic

Figure 16 ‐ Considerations for Pedestrian Facilities

F. Bicycle Facilities

Developing or improving bicycle facilities often means coordinating improvements with street projects. Adding or improving bicycle lanes can require construction, such as resurfacing or improvements to a streets shoulder and moving or changing storm drains to bicycle friendly storm drains. Bicycle lanes can also cause a need for repainting and striping along with signage to improve space and drivers awareness of bicyclists. Other considerations such as the placement of bicycle racks are also important for bicyclists to reduce the worry and willingness to lockup their valuable bicycle. Valuable information and sources on providing bicycle facilities can be found at bicycleinfo.org

Other improvements for bicycle facilities include:

•

Traffic control devices

•

Traffic calming

•

Bicycle parking

•

Bicycle lockers

29

•

Park‐and‐ride lots

G. Complete Streets\Livable Communities

Complete Streets and Livable Communities expand on the base of pedestrian and bicycle network design. Complete Streets consider the entire environment of the pedestrian and bicyclists, for example, trees are planted where its hot, traffic calming is placed where traffic is fast, and adding furniture when possible. When designing a complete street more attention is given to the pedestrian and bicyclist, and considerations are made on a case‐by‐case measure.

H. Local Ordinances

Municipalities and other local forms of government have the ability to create and modify local ordinances in order to provide safety or create design standards for the pedestrian or bicyclist. These ordinances can require property owners to clear their sidewalks of snow in winter, allow children to ride their bicycle on the sidewalk, or require bicycle parking at businesses. The use of ordinances can be helpful in creating a proper environment for the pedestrian and bicyclists when ordinances are followed and enforced. There is little information of local ordinances for the pedestrian and bicyclist and no model ordinances where found in this research.

I. Prioritizing Improvements

When prioritizing improvement projects there are a few factors to be considered. To keep things simple; demand, barriers, benefits, and costs can help

30

determine a sequence for creating and improving pedestrian and bicycle systems.

These factors have been used to create simple and complete matrix systems to determine priorities. An example of a matrix system can be found in the Victoria

Transport Policy Institute’s Pedestrian and Bicycle Planning: A Guide to Best

Practices . Another way to stage pedestrian/bicycle facility improvements and new construction is by requests and complaints, and cities such as Portland refer back to transportation and neighborhood plans as part of their process.

Prioritizing improvements and new constructions can also become a complex system, taking in consideration multiple variables like those discussed in the

AASHTO Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian Facilities . This guide provides a list of variables and describes their importance for consideration for improvement projects. Other thoughts and ideas can be found by getting public involvement to determine the areas interests and values; there may be areas that neighborhood wish to have higher priority.

31

AASHTO's Variables for Priority in Retrofitting

Volume

Pedestrian Generators

Road Traffic Speed

Street Classification

Crash Data

School Walking Zones

Transit Routes

Urban Centers

Neighborhood Commercial Areas

Disadvantaged Neighborhoods

Missing Links

Neighborhood Priorities

Activity Type

Transportation Plan Improvements

Citizen Request

Street Resurfacing Programs

Figure 17‐AASHTO’s Variables for Priority in Retrofitting

Source: AASHTO Guide for the Planning, Design, and Operation of Pedestrian

Facilities

J. Sample Pedestrian and Bicycle Plans

When beginning to plan or revise a pedestrian/bicycle plan it can be very helpful to review other plans that are new and well planned. Reviewing other plans can be helpful by observing good examples in areas that are unfamiliar, or by learning a new concept or idea that may not have been thought of or covered in the previous plan. There are no comprehensive lists or rankings of pedestrian or bicycle plans, but there have been some attempts to try to provide useful lists.

Walkinginfo.org and bicyclinginfo.org both have long lists of plans one can review.

They also separate plans into state, regional, local, trail/greenway, and site plans to try to be more helpful. Another great source is in the appendices of the continually revised Pedestrian and Bicycle Planning: A Guide to Best Practices produced by the

32

Victoria Transportation Policy Institute. For this guide, the writers have provided a list of plans that were reviewed and were thought to be exemplary.

9. Coordination Needed

During and after work on a pedestrian/ bicycle plan, coordination is needed between the pedestrian/bicycle planner and other officials and departments along with the public. The public works and their street departments will play an important part in the implementation, maintenance, and design of any pedestrian and bicycle plan. Many others may have valuable information and input on things such as rules, regulations, funding, current and future projects, and zoning.

Coordination helps to keep everyone in the loop, benefits with participant’s recommendations, and having everyone on the same page help in its implementations. This topic has been discussed in multiple pedestrian and planning documents including the Federal Highway Administration’s book Implementing

Bicycle Improvements at the Local Level .

33

MUNCIE’S EXISTING PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE PLAN

Muncie’s pedestrian plan is part of a countywide plan as it has been developed from a city‐county planning department, the acting Metropolitan

Planning Organization (MPO). The Delaware‐Muncie Metropolitan Plan Commission created its first bicycle plan in 1995 and bicycle/pedestrian plan in 2000. These plans were meant to be to a jumping off point for an anticipated plan called

Community Connections. In 2005 the latest transportation plan incorporated and updated the bicycle/pedestrian plan with information and references to the

Community Connections plan. However, there was a problem with the Community

Connections plan. The company that was contracted to produce the plan had some management issues and split up during the production of the document, thus, reducing its quality. This has delayed progress in improving Muncie’s pedestrian and bicycle network. The Delaware‐Muncie Metropolitan Plan Commission is currently in progress on updating the 2005 Bicycle/Pedestrian Plan to be released sometime in 2009.

As the Muncie‐Delaware Metropolitan Plan Commission covers most of

Delaware County the current plan covers goals and objects meant to allow anyone within the county to reach the Pedestrian/Bicycle network. Because there is a

34

countywide focus, projects and their priority are not focused entirely on the city.

Being a countywide plan, the criteria noted below was suggested to help in the planning process. With this criterion a new system was to be proposed using new and existing facilities.

Delaware-Muncie Transportation Plan Classification Variables for Sidewalk

Projects Priority

Connectivity

Development Density

Land Use Type

Level of Service (LOS)

Projected Use

Safety

Congestion

Modal Conflict Resolution

Accidents

Hazardous Segments

Pedestrian/Bicycle Volume

Figure 18 – Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan Classification Variables for

Sidewalk Projects Priority

Source: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan

With the completion of the Community Connections plan an inventory and analysis of the current system with recommendations was produced. This was completed with the use of a new geodatabase created for this project. With the geodatabase and geographic information systems (GIS) software the existing conditions, improvements, and future proposals were all geographically represented with easy interpretation. This was very useful for the county when

presenting and collecting input from the community.

The Community Connection plan was also meant to provide recommendations and guidelines for local officials, so they would have the correct

35

tools for implementing the new network. Guidelines for right‐of‐ways, design standards, and maintenance recommendations were to be created. In all, the plan was to be the beginning of a new strong multi‐modal system for Muncie and

Delaware County. Unfortunately Murphy’s Law stepped in with the contractor and the Community Connections plan never became the large stepping‐stone that it

should have been.

36

The following are maps and descriptions are from the Community Connections plan.

Figure 19 – 20052030 DelawareMuncie Transportation Plan. Page 39

Figure 9 is a map of proposed routes initially developed from data and further developed with input collected over several public viewing sessions. This map was created for the Community Connections plan. Other information about the map and routes are unknown.

Figure 20 – 20052030 DelawareMuncie Transportation Plan: Project

Priority. Page 40

Figure 10 is a mapping for a list of 12 proposed multi‐use pathways, developed as part of the Community Connections plan. These projects were chosen based on public input, mostly from Muncie. Most participants were located in

Muncie, all there most projects are found to be centrally located around Muncie.

This causes concern, as it seems to acknowledge that the public living outside the city were not represented and were given no consideration in the development in

the list of priority projects. The following is a list of the projects and their identification number to help refer between the map on Figure 10 and the table in

Figure 11.

37

List of Project Priorities for Figures 10 & 11

1 Morrow's Meadow Trail/White River Greenway

2 Buck Creek Beltway

3 Campus Connector

4 Muncie Creek Greenway

5 York Prairie Greenway East

6 Central Levee Walk

7 Bethel Heron Trail/ Evermore Path

8 River Road Greenway

9 White River Greenway Memorial Extension

10 Rosewood Farm Pathway

11 York Prairie Greenway West

12 Beach Grove Greenway

Figure 19‐List of Project Priorities for Figures 10 & 11

Source: 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan

38

39

Figure 21‐ 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Project Priority

40

Figure 22‐ 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Project Priority &

Other Path Costs

Figure – 11

The costs in this table were preliminary estimated costs at $300,000 per mile for multi‐use paths. The costs were the base prices with no additional costs estimated for changes in design or engineering.

41

Figure 12 20052030 DelawareMuncie Transportation Plan:

Pedestrian/Bicycle and Roadway Coordination Project. Page 43

Figure 12 is a mapping of pedestrian and bicycle facilities that are priorities for new construction or replacement during scheduled or foreseen roadway projects. The facilities listed on the map were determined with data layers, public input, and the need to fill in missing segments of the network. The map also shows projects where coordination for new or replacement pedestrian/bicycle facilities have been made.

Figure 13 20052030 DelawareMuncie Transportation Plan:

Pedestrian/Bicycle Network Water Crossings. Page 44

The White River is a beautiful meandering river that runs its way through

Muncie, IN creating a need for many water crossings for the pedestrian/bicycle network. Figure 13 is a map of Muncie the location of water crossings for the White

River and the many other creeks and drainage ditches.

Figure 14 20052030 DelawareMuncie Transportation Plan: Sidewalk

Priority Areas. Page 45

This Figure is a simple map show that shows the areas where there is a priority for sidewalk construction. The areas shown are the top six area, in no order.

None of the areas are in the study area for this project.

42

Figure 23 ‐ 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Pedestrian/Bicycle and Roadway Coordination Project.

43

Figure 24 ‐ 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Pedestrian/Bicycle Network Water Crossings

44

Figure 25 ‐ 2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan: Sidewalk Priority Areas

45

DATA COLLECTION

Data collection began with researching existing documentation and data available. Documentation on the current pedestrian/bicycle network was discussed in detail in the previous chapter. The Muncie‐Delaware Plan Commission held the

2005‐2030 Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Plan, Community Connections Survey

Results, and Delaware‐Muncie Transportation Improvement Program. Attempts were made to view the 1995 Transportation Plan, the 2000 Transportation Plan and the Community Connections plan, but were these documents were never made available. The Delaware County Geospatial Resources Office (GIS Office) provided many helpful geospatial datasets listed below. The GIS data made available were created by the GIS Office with the exception of the Census and Sidewalk Conditions datasets. Multiple offices were also asked for a transition plan regarding ADA

compliance, but this document was never made available.

Delaware County Geospatial

Resources’ GIS Data:

Alleyways

Building Footprints

Bus Routes and Stops

Census Data

Land Use

Parcels

Parks

Schools

Sidewalk Condition

Streets

Water Bodies

Sewer Facilities

Figure 26 – Delaware County Geospatial Resources’ GIS Data

For more input on the creative project a meeting was set up with Marta

Moody, Executive Director of the Delaware‐Muncie Plan Commission and another interested party. Common interests were discussed. Ms. Moody also shared recommendations made by other groups that were looking to improve the pedestrian system in Muncie’s Historic Downtown and elsewhere.

After review of the existing data and discussion with other parties, it was determined that additional data and updated information was needed. The sidewalk data was outdated and did not represent the current sidewalk conditions.

The data was also lacking other useful information such as sidewalk distance to the curb and buffer type. Other information thought to be useful such as, barriers and hazards would also need to be collected. A new survey of the sidewalk was needed.

ESRI ArcPad and ArcView were selected to create, collect, and analyze the data. A personal geodatabase was created with a shape and point file to develop the feature and input data being surveyed. Each surveyed feature was given a field and

47

domains were added to allow for a better efficiency while in the field. In addition, a

“notes” field was added in order to enter information not covered by the other variables being surveyed.

The survey identifies physical features for the pedestrian network. The potential features and their descriptions are listed on the following page. The primary need for the survey was to analyze Muncie’s Downtown and its surrounding area and streets that could be used as connections to the downtown.

For consistency, the criteria was developed for determining sidewalks

conditions. The criteria noted on the survey, found on the following page, were developed for simplicity and to meet the needs of this project. Following the survey

are reference material created to provide visual examples.

48

2009 Sidewalk Survey

Sidewalk Conditions

Rating Condition

1 Excellent

2 Good

3 Fair

4 Poor

Description

Like new

Few bumps or cracks

Some bumps or cracks, some heaving of the sidewalk

Lots of bumps or cracks, lots of heaving

5 None

Sidewalk Width

Range Unit

No existing sidewalks

0' - 30' Feet

Sidewalk Distance to Curb

Range Unit

0' - 16' Feet

Buffer Type Between Sidewalk and Curb

ID Description

1 Grass

2 Brick

3 Landscaping

4 Hedges

5 Trees

6 Concrete/Landscaping

7 Other

Curb Cut North or West

ID Description

1 Yes

2 No

Curb Cut South or East

ID Description

1 Yes

2 No

Barrier Type

Unit Description

1 Utility pole

2 Street tree

3 Street sign

4 Fire hydrant

5 Curb cut/ramp in bad condition or not ADA compliant

6 Utility cabinet

7 Utility pole guy wire

8 Street light

Figure 27‐ 2009 Sidewalk Survey

49

Excellent Condition

‐ New or Perfect Condition

No bumps, cracks, or heaving.

Figure 28‐ Sidewalk Condition “Excellent”

Good Condition

‐Like New

Few bumps, cracks, and little heaving.

Figure 29‐ Sidewalk Condition “Good”

50

Fair Condition

‐Older Condition that may need repairs, but not yet in need of

replacement

Some bumps, cracks, or heaving.

Figure 30‐ Sidewalk Condition “Fair”

Poor Condition

‐ Conditions that are in need of replacement

Major bumps, cracks, or heaving.

Figure 31 – Sidewalk Condition “Poor”

51

Figure 32 – Sidewalk Condition “None”

None

‐ No Sidewalk Present

Sidewalk not present or no longer function

Figure 32‐ Sidewalk Condition “None”

For the survey, data was collected on an Xplore tablet PC with ESRI’s ArcPad for accurate positioning. Data for the survey was collected by walking all the sidewalks and areas where there is potential to develop sidewalks. Figure 33, shown on page 52, shows the entire area surveyed. The data was inputted into the geodatabase with ESRI’s ArcPad software. To collect the measurements needed a measuring wheel was used to get rough estimates within ¼ of a foot or better. The data was collected by one person, eliminating inconsistencies of multiple persons on the judgment of sidewalk conditions. Surveying the area took over two weeks, but could have been shorter if not for the limitation made by the Xplore tablet PC. The tablet could only hold a charge that varied between 105 minutes and 180 minutes

52

(1.75 – 3 Hours). There also were no additional batteries, so there was a similar wait period while the Xplore tablet was charging.

After the data was collected, the information was cleaned and corrected to fix overlaps, GPS error, and make adjustments based on notes taken by the survey. An addition was made to add hazards to the list of barriers. While conducting the survey many street signs were removed incorrectly leaving jagged metal to stick out of the concrete. Additional barriers included old bolts left in the concrete after some type of streetlight or other pole was removed. Some areas even had wiring and fragments of old poles.

53

Sidewalks Surveyed

Figure 33 – 2009 Sidewalks Surveyed

54

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

In conducting the survey and analyzing the data, important information was collected and several issues were discovered. The information collected with the

GIS system provided very useful data that is visual as well as analytical. By displaying the survey data and data collected from the GIS office on a map one can quickly interpret the data, identify concerns and area for improvement, and envision new routes and connections.

According to the survey findings on sidewalk condition, about 82 percent of the sidewalks were in “fair” condition or better. Eighty‐two percent is an exact percentage when looking at each segment of sidewalk and its condition. In a downtown where pedestrian access is a high priority, 82 percent can still be viewed as a low number.

When looking at a city block that is in

“excellent” condition with exception of a small, heaved segment of sidewalk, the

condition then becomes “poor” as a person with a disability may find the sidewalk of the entire block unusable. When looking at the entire length of a block to determine conditions, a larger percentage of sidewalk becomes identified to be in less than useful condition. that is in a less than useful condition. Look at the entire length of the block and assign the entire block the lowest condition when Poor or None conditions are present or when driveways have no curb ramp only about 53.5

percent of the sidewalks are walkable for the entire population. The length in feet and percentages are shown below and maps are show on pages 61 and 62.

Sidewalk Segment Conditions

Condition Feet Percentage

Excellent 32,103.49

24.92%

Good 43,032.53

33.40%

Fair

Poor

30,331.75

19,557.68

23.54%

15.18%

None 3,820.24

2.96%

Total 128,845.70

100.00%

Figure 34 ‐ Sidewalk Segment Conditions

City Block Sidewalk Conditions

Condition Feet

Excellent 26,295.04

Percentage

20.41%

Good

Fair

Poor

None

26,911.72

15,763.38

55,269.67

4,605.89

20.89%

12.23%

42.90%

3.57%

Total 128,845.70

100.00%

Figure 35‐ City Block Sidewalk Conditions

A second area of importance is the type or design of the curb ramps. While conducting the survey, it was found that more information should have been collected in this area. The ADA standards for curb ramps, in the Public Right‐of‐Way

56

Accessibility Guidelines, have not yet been accepted and currently use ramp standards found in other sections of the Act. The standards currently in draft form will create a higher standard than that found in Downtown

Muncie. Information, such as width of the curb ramp, warning strip type, warning strip width, warning strip color, and ramp grade, would have been valuable information to have when the Public Right‐of‐Way

Accessibility Guidelines are adopted. The data collected was only to find whether there was a curb along a pedestrian route. Of the 790 points where a pedestrian route intersects a curb, 684, or about 87 percent, had ramps. Condition and design of the ramps were not considered. The fact that there was or was not a ramp was the only variable in the decision. The following table shows the data collected from the survey on curb ramps.

Curb Ramps

Yes

No

Total

Count Percentage

684 86.58%

106

790

13.42%

100.00%

Figure 36 – Curb Ramp Counts

Additional information was collected on barriers and hazards on pedestrian routes. Along a pedestrian route there are many items that a pedestrian must interact and maneuver around. The survey collected points for barriers and hazards to find the number of interactions or maneuvers one would make along a route.

Many items were found, including many unexpected hazards. Old parts from

57

streetlights and signposts were found in the sidewalk. Bolts, jagged signposts, broken bases of streetlights, and sawed down utility

poles were all found. Pleas see the data below for specific information.

Conflict Points

Count

Bad Ramp

Concrete Block

Fire Hydrants

Guy Wire

Hazards

Mail Box

No Curb Ramp

Other

Plants

Railings

Sidewalk Heaves

Sign Stubs

Stairs

Street Lights

Street Signs

Traffic Light

Trees

Utility Box

Utility Poles

Xing Light

Total

Figure 37 – Pedestrian Barriers and Hazards Count

94

123

28

117

36

1230

73

40

12

10

20

15

195

264

6

6

73

35

23

12

48

58

Visualizing data can help one grasp issues or envision new ideas. The following pages in this chapter are maps produced from the survey. Descriptions are included for each map.

Figure 38 – Detailed Sidewalk Conditions

The map of detailed walking conditions, as it implies a detailed map of walking conditions. The survey taken was meant to extract data regarding the condition of sidewalks within the study area and along neighborhood connections.

Figure 39– Generalized Sidewalk Conditions

This map was meant to illustrate the sidewalk conditions from the viewpoint of an individual with physical disabilities. In this case, when a segment of a block was missing or in poor condition, the entire block was reassigned as “none” or

“poor” condition. Additionally, a block of sidewalk with a curb and no ramp was reassigned a “poor” value. In this way, a better visualization can be made concerning routes that are either accessible or restrictive to individuals with physical disabilities.

Figure 40– Points of Conflict

Walking down a sidewalk in the Downtown one will have to maneuver around many objects that are presently in the walkway. This is not a significant problem for many of us, but individuals with visual impairments be slowed by related hazards. Guy wires that stabilized utility poles can cause hindrances, or even serious injuries. Many of these points of conflict can be replaced to less intrusive

59

locations or eliminated from the walkway. This map shows where there are large groupings of hazards and provides a visual of the points of conflict.

60

Detailed Sidewalk Conditions

Figure 38 – Detailed Sidewalk Conditions

61

Generalized Sidewalk Conditions

Figure 39– Generalized Sidewalk Conditions

62

Points of Conflict

Figure 40– Points of Conflict

63

DOWNTOWN MUNCIE PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLE PLAN

The pedestrian and bicycle plan for Downtown Muncie is one recommendation needed to rejuvenate the Downtown into the active city center it once was. The Purpose of these changes is to encourage walking and bicycling into preferred and efficient modes of transportation used in the Downtown (shown in

Figure 1A). By expanding on and improving the current pedestrian and bicycle network, not only will Muncie regain an underutilized mode of transit, but also gain benefits in many other areas, such as public health, economic, transit, quality‐of‐life, environment, and energy.