SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT AT A PUBLIC UNIVERSITY: PRECEDENT, PROGRESS, AND POTENTIAL

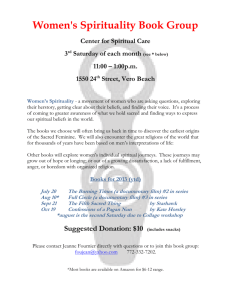

advertisement