CHORAL REPERTOIRE SELECTION EXPERIENCES REQUIRED OF

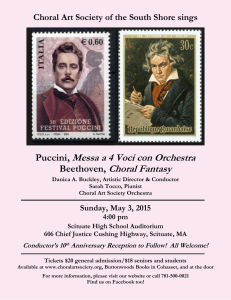

advertisement