“IN ORDER TO ACCOMPLISH THE MISSION:”

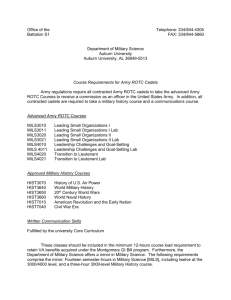

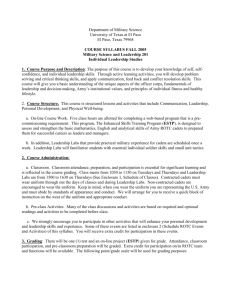

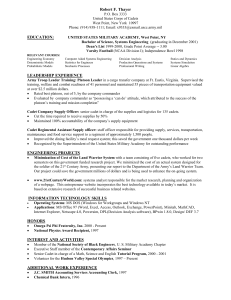

advertisement