SPIRITUALITY IN THE TERMINALLY ILL HOSPITIZED PATIENT A RESEARCH PAPER

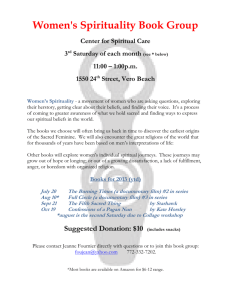

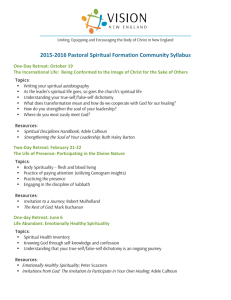

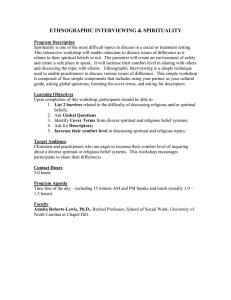

advertisement