Document 10909516

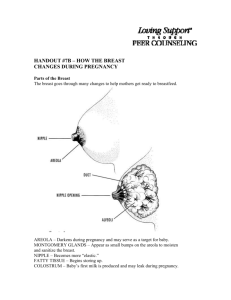

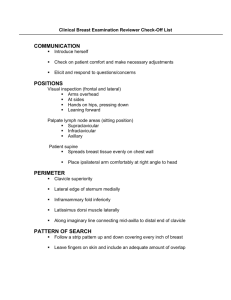

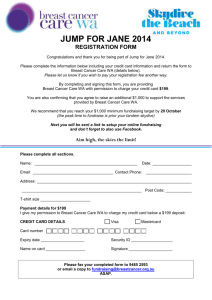

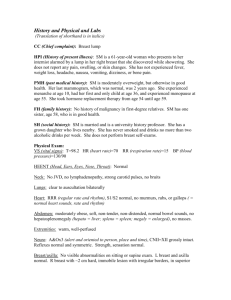

advertisement