Running Head: PHYSICIAN ADHERENCE Physician Adherence to Communication Tasks with

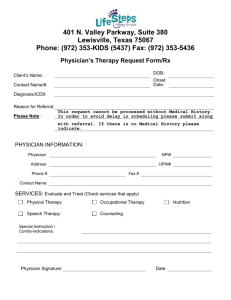

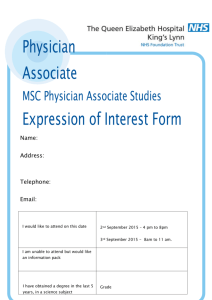

advertisement