Quantifying the Current and Future Impacts of the MBTA Corporate Pass

Program

by

Dianne E. Kamfonik

Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering

Cornell University, 2010

Submitted to the department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

ARCHfM

CHUSETTS

OF TECHNOLOGY

Master of Science in Transportation

JUL 08213

at the

LIBRARIES

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 2013

@2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved.

Author.r............................

t

f Civil and Enioninal Engineering

May 23, 2013

C ertified by ...........................................

Research Asso iate of

Certified by ............................ .

.........

......

.

ivil and

. .

.........

John P. Attanucci

vironmental Engineering

Thesis Superyisor

...............

...

....

.

v.

Frederick Salvucci

Senior Lecturer of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Thens Supervisog

Accepted by.........................................................

Heidi N. Ne

Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students

E

Quantifying the Current and Future Impacts of the MBTA Corporate Pass

Program

by

Dianne E. Kamfonik

Submitted to the department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

on May 23, 2013 in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Science in Transportation

Abstract

Many city and regional transportation authorities, including the Massachusetts Bay Transportation

Authority (MBTA) in Boston, offer a monthly pass to local employers which they can distribute to

their employees. There are many ways in which an agency, employer or individual benefit from an

employer pass program. There are financial benefits for all three parties, as well as increased

convenience for employees, better travel demand management for employers, and increased

ridership for agencies.

The MBTA Corporate Pass Program was established almost forty years ago in an attempt to

move away from inefficient fare collection methods while providing an avenue for employers to

contribute to their employees' transit commutes and increase transit ridership generally. With

these intentions in mind, this thesis aims to analyze the MBTA's employer pass program, and to

quantify its benefit to the MBTA through program penetration, additional revenue captured, and

reduced sensitivity to fare increases and seasonal fluctuations. Influencing factors such as company

location, subsidies and local city policies are also analyzed to determine the effects of employer

benefits policies on an employee's participation in the Corporate Pass Program and their transit

ridership.

The results show that the Corporate Pass Program is a very positive program for the MBTA, and

accounts for 27% of their annual revenue. The MBTA receives an estimated additional $4.4 million

in potentially foregone revenue from LinkPass Corporate pass holders annually. The program

captures additional revenue by appealing to employees with lower transit usage than the average

pass holder, many of whom do not use the aggregate ride "value" of the pass in most months and

are attracted to the program because of the pretax or employer-provided subsidies. Furthermore,

the Corporate Pass Program provides greater revenue stability month to month than other types of

monthly passes as its users are less likely to cancel its purchase for vacation months than retail

month to month users. This research also finds that certain employer characteristics, such as size,

pass subsidy, location and parking availability have clear influences on employee participation and

more subtle influences on average employee ridership.

Thesis Supervisor: John P. Attanucci

Title: Research Associate of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Thesis Supervisor: Frederick Salvucci

Title: Senior Lecturer of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Acknowledgements

John Attanucci and Fred Salvucci, thank you for your guidance and for all of the time, effort and

energy you dedicated to this research. I have learned so much from both of you.

David, your support, editing skills, and insight have been unbelievably helpful over the past two

years.

Thank you to Nigel Wilson and all of the students and professors in the MIT Transit Lab. I truly

enjoyed working with and learning from each and every one of you.

Ginny, thanks for keeping us all on track.

A warm thank you to everyone at the MBTA for encouraging our work and sharing your data,

especially Rob Creedon, Lynne O'Neill, and Josh Robin. Thanks also to Candice Brakewood for

getting us an office.

This research would not have been possible without the help of the over 500 survey responses

from employers across the Boston area. Thank you all for providing the data for this analysis, and

for your candid and helpful feedback.

Above all else, thank you to my family-Mom, Laura, & Ollie-for your unwaivering support.

Eric, I'm not sure what to say because "thank you" doesn't quite seem to cut it.

5

6

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1

B ackground . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

1.2

Problem Statement

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

1.3

Research Objectives and Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

1.3.1

Employer Practice Survey

28

1.3.2

Corporate Pass Holder Usage Analysis

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

29

1.3.3

Influences on Participation and Usage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

1.4

2

19

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Organization of This Thesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Literature Review

33

2.1

Commuter Benefits Overview

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

33

2.2

History of Commuter Benefits

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

2.3

Evaluating and Improving Commuter Benefits Programs

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

2.4

History of the MBTA Corporate Pass Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

2.5

MBTA Fare Structure and Current Corporate Pass Structure . . . . . . . . . . . . .

43

2.5.1

MBTA Fare Structure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

43

2.5.2

Corporate Pass Program Structure and Third-Parties

44

. . . . . . . . . . . .

2.6

The Mobility Pass Trial at MIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

2.7

Comparison to Other Employer Pass Programs

2.7.1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

City 1: Washington, DC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

7

3

4

2.7.2

City 2: San Francisco, CA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

2.7.3

City 3: Philadelphia, PA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

2.7.4

City 4: Seattle, WA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

2.7.5

Lessons Learned from Employer Pass Program Comparison

. . . . . . . .

54

Investigating the Current MBTA Corporate Pass Program

57

3.1

58

Employer Practice Survey

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.1.1

Location

3.1.2

Availability of Pretax Purchase of Passes

3.1.3

Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

3.1.4

Parking Availability and Cost

3.1.5

S ize . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 1

3.1.6

Industry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

3.2

Employee Participation Rate

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

3.3

Employer Market Penetration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

84

3.3.1

Large Employers in Boston and Cambridge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

84

3.3.2

Estimate of Revenue From Non-Subscription Third-Party Benefits . . . . .

88

3.3.3

Within a Walkable Distance of Transit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Corporate Pass vs. Non-Corporate Pass Usage and Revenue Comparisons

93

4.1

Usage Analysis Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

4.2

LinkPass Monthly Usage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

4.3

Monthly Bus Pass Usage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

4.4

Monthly Commuter Rail Pass Usage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

4.5

Fare Increase Effects: Revenue and Usage Over Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

4.6

4.5.1

Pass Sales Over Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

4.5.2

Usage Over Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

Summary of Corporate vs. Non-Corporate Usage and Revenue . . . . . . . . . . . 115

8

5

Effects of Employer Benefit Policies and Other Characteristics on Employee

Participation and Usage

5.1

Participation of Employees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117

5.1.1

A Priori Expectations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

5.1.2

Employer Characteristics at a Glance

5.1.3

Examining the Combined Effect of Employer Characteristics on Employee

Participation

5.1.4

5.2

5.3

6

117

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

Participation Results

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

Average Employee Usage Levels of a Corporate Monthly Pass

. . . . . . . . . . . 141

5.2.1

A Priori Expectations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142

5.2.2

Employer Characteristics at a Glance

5.2.3

Regression Analysis

5.2.4

Average Employee Usage Results

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154

Lessons Learned: Effects of Employer Characteristics on Participation and Usage . 156

Employer Feedback on the MBTA Corporate Program

159

6.1

Ordering Timeline Issues (19%)

6.2

Billing/Payment (17%) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 162

6.3

CharlieCard Issues (15%) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

6.4

Paper Ticket Issues (15%)

6.5

Service, Communication and Information (14%) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 168

6.6

Website (7%) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 170

6.7

O ther (6% )

6.8

Should be Discounted (4%) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

6.9

Entire Program (3%)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 171

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

6.10 Conclusions on Customer Feedback

7

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

Conclusions and Recommendations

175

9

7.1

Summary and Findings . . . . . . . . . .

175

7.2

Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . .

178

7.2.1

Future Marketing . . . . . . . . .

178

7.2.2

Role of Third Parties . . . . . . .

181

7.2.3

Response to Feedback

. . . . . .

184

Future Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

186

7.3

Appendices

189

A Example Tax Calculations

191

B Employer Practice Survey Questions

197

C July 2012 MBTA Fare Increase Details

199

D Table of U.S. Transit Agencies and Characteristics

203

E Mobility Pass Report

205

F Commuter Rail Average Usage in Days for April through November 2012

213

G Participation Regression Analysis Iterations

219

H Usage Regression Analysis Iterations

225

Bibliography

235

10

List of Figures

1.1

Basic Employer Pass Program Structure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.2

Monthly Pass Sales and Corporate Monthly Pass Sales as a Percentage of Total

21

Sales Revenue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

26

2.1

Transportation Benefits Caps From 1992 to 2013

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

2.2

Commuter Check@ Company Savings Calculator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

2.3

Diagram of the Current Corporate Pass Program Distribution System . . . . . . . . 45

3.1

Representativeness of Sample

3.2

Distance to CBD

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

59

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

3.3

Corporate Pass Program Employer Distance to Closest Subway Station . . .

62

3.4

Corporate Pass Program Employer Distance to Closest Subway Station (only those

w ithin 0.5 miles)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

3.5

Distribution of Subsidies by Employer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

3.6

Distribution of Subsidies by Employee . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

3.7

Employer Subsidies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

3.8

Employer Parking Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

3.9

Employee Parking Access

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

69

3.10 Parking Subsidies by Employer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

3.11 Parking Subsidies by Employee

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

3.12 Company Size for All Direct Corporate Pass Program Employers . . . . . . . . . . 73

11

3.13 Company Size for Direct Corporate Pass Program Employers

Employees or Fewer

with

1000

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

73

3.14 Distribution of Company Size for All Direct Corporate Pass Program Employers as

a Percentage of the Number of All Employers in Suffolk, Norfolk and Middlesex

Counties of the Same Size

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

74

3.15 Corporate Pass Program Employers by Industry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

3.16 Employees with Corporate Pass Program Access by Industry . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

3.17 Distribution of Industry Classification for All Corporate Pass Program Employers

as a Percentage of All Employers in Suffolk, Norfolk and Middlesex Counties

W ithin the Same Industry . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

3.18 Distribution of Industry Classification for All Employees with Access to the

Corporate Pass Program as a Percentage of All Employees in Suffolk, Norfolk

and Middlesex Counties Within the Same Industry

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

3.19 Employee Participation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

82

3.20 Participation Rates by Employer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

3.21 Employee Participation by Employer Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

3.22 Benefits Offered to the Employees of the Top 25 Largest Employers in Cambridge

and B oston

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

85

3.23 Estimated Benefits Offered to the Employees of the Top 25 Largest Employers in

Cambridge and Boston (50 companies combined) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

87

3.24 Estimated Penetration of Transit Benefits for Employees of Top 25 Largest

Employers in Cambridge and Boston . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

88

3.25 Estimated Penetration of Transit Benefits for All Employees within 0.5 Miles of a

Rapid Transit Station . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

91

3.26 Dot Density of Active CharlieCards and All Employers within 0.5 Miles of a Rapid

Transit Station . . . . .

4.1

- . . . ... .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

July 2012 and November 2012 Unlinked Trips for LinkPass Users . . . . . . . . . 98

12

4.2

Comparison of April and May 2012 Usage vs. Revenue for Corporate and NonCorporate LinkPasses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

4.3

Local Bus Pass July 2012 and November 2012 Unlinked Trips . . . . . . . . . . . 104

4.4

Comparison of April and May 2012 Usage vs. Revenue for Corporate and NonCorporate Local Bus Passes . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . 105

4.5

Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subway Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

4.6

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Buses and Subways . . . . . . . . . 109

4.7

2012 LinkPass Unit Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

4.8

2012 Monthly Bus Pass Unit Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .111

4.9

2012 Commuter Rail Pass Unit Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .111

4.10 LinkPass Usage Before and After Fare Increase . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

4.11 Bus Pass Usage Before and After Fare Increase

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

5.1

Employee Participation Rate by Distance to CBD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

5.2

Participation Rate within 0.25 Miles of Bus or Subway

5.3

Participation Rate within 0.5 Miles of Bus or Subway . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

5.4

Participation Rate within 0.25 and 0.5 Miles of Subway Station . . . . . . . . . . . 123

5.5

Participation Rate by Location in Cambridge or Elsewhere

5.6

Participation Rate by Location in Cambridge or Elsewhere (1-6 Miles from CBD) . 125

5.7

Participation Rate by Pretax Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

5.8

Participation Rate by Subsidy Amount . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

5.9

Participation Rate by Existence of Employer Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

5.10 Participation Rate by Parking Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

5.11 Participation Rate by Parking Availability (Yes or No) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

5.12 Participation Rate by Parking Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

5.13 Participation Rate by 9 Company Size Categories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

5.14 Participation Rate by 4 Company Size Categories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

13

5.15 Participation Rate by 4 Company Size Categories Among Companies with No On-

Site Parking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

5.16 Participation Rate by 4 Company Size Categories Among Companies with On-Site

P arking

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . 134

5.17 Participation Rate by 4 Company Size Categories Among Companies within 0.5

M iles of a Subway Station

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

5.18 Participation Rate by 4 Company Size Categories Among Companies Between 0.5

and 1 M iles of CBD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

5.19 Average Usage by Distance to CBD

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 144

5.20 Average Usage by Distance to Subway . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

5.21 Average Usage by Location in Cambridge or Elsewhere . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146

5.22 Average Usage by Pretax Availability

5.23 Average Usage by Subsidy Amount

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

5.24 Average Usage by Existence of an Employer Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149

5.25 Average Usage by On-Site Parking Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150

5.26 Average Usage by Parking Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

5.27 Average Usage by Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

6.1

Employer Feedback by Topic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

6.2

Screenshot of "Payment Meth ods" Page of Corporate Pass Website . . . . . . . . . 165

7.1

Employee Tax Savings Calculator

F. I

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - April 2012

F.2

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - May 2012 . . . . 214

F.3

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - June 2012 . . . . 214

F4

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - July 2012 . . . . 215

F.5

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - August 2012 . . 215

F.6

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - September 2012

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

. . . . . 181

. . . 213

216

F.7

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - October 2012 . . 216

F.8

Comparison of Commuter Rail Pass Usage on Bus and Subways - November 2012

15

217

List of Tables

1.1

Passenger Fares by Mode, Report Year 2010 (Dickens, Neff, & Grisby, 2012)

2.1

MBTA Single-Fare and Pass Pricing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

2.2

Third Party Commuter Benefits Providers Available to San Francisco Employers

50

2.3

Comparison of ORCA Commuter Pass Options

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

3.1

Employer Proximity to Subway Station

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

3.2

Subsidy Statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

3.3

Employer Size Statistics

3.4

Company Size Shown by Parking Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

4.1

Corporate LinkPass Unlinked Trips vs. Non-Corporate LinkPass Unlinked Trips -

. . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

July Through November 2012

20

72

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

4.2

Usage Comparison of Direct Customers to Third-Party Subscription Customers

.

102

4.3

Monthly Bus Pass Usage Comparison of Unlinked Trips: April-November 2012

.

103

4.4

Commuter Rail Pass Usage in the Subway and Bus System . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

4.5

Average Monthly Total LinkPass Trips Before and After the July 2012 Fare Increase 114

4.6

Average Monthly Total Bus Pass Trips Before and After the July 2012 Fare Increase 114

5.1

Participation Regression Results - Excluding Parking Subsidy

5.2

Participation Regression Results - Including Parking Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

5.3

Usage Regressions Results - No Parking Subsidy

5.4

Usage Regressions Results - Including Parking Subsidy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

16

. . . . . . . . . . . 138

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152

D. 1

15 Urbanized Areas with the Most Transit Travel, Ranked by Unlinked Passenger

Trips, Passenger Miles, and Population, Report Year 2010

17

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 204

18

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1

Background

Transit agencies around the world offer a wide variety of payment options, often including cash

single and multi ride tickets, period passes, and stored value cards, often with discounts available to

certain people such as seniors, students and monthly customers. In terms of unlimited use period

passes, there are daily passes, weekly passes, monthly passes, and even annual passes. A few

agencies even offer guaranteed best pricing, meaning passengers "pay as they go" only until they

reach a pre-determined cap for a set period. In the United States, fares are collected in a wide

variety of different ways, some of which are shown in Table 1.1 below (Dickens, Neff, & Grisby,

2012).

The choice to offer an unlimited pass, and the pricing thereof, is an important component of

a transit agency's fare structure. An unlimited pass is beneficial to customers in the sense that it

can be cost-effective if their single-ride fares would sum to greater than the price of the pass. A

pass also has the additional benefit of providing transit to customers at zero marginal cost once it

is purchased. This provides greater accessibility to customers as they may choose to take more

transit trips simply because it is free for them to do so.

In general, employer pass programs are a method through which transit agencies can sell transit

19

Bus

Commuter Demand

Rail

Re-

Heavy

Rail

Light

Rail

Trolleybus

Total

sponse

Passenger Fares,

Millions of

4,997.3

2,248.7

485.7

3,965.7

412.2

80.1

(b)12,556.1

$0.95

$4.84

$2.56

$1.12

$0.90

$0.81

$1.23

$7.00

$25.00

$6.25

$2.25

$2.50

$2.25

$25.00

$1.53

$6.66

$2.31

$1.95

$1.87

$1.50

$1.97

$1.50

$3.75

$2.50

$2.00

$2.00

$1.88

$1.75

$0.00

$2.25

$0.00

$1.40

$1.00

$0.00

$0.00

6.0%

21.4%

NA

7.7%

14.3%

25.0%

6.3%

28.1%

0.0%

NA

46.2%

33.3%

100.0%

30.1%

23.9%

57.1%

NA

30.8%

23.8%

0.0%

19.9%

21.6%

21.4%

NA

61.5%

33.3%

25.0%

24.6%

55.3%

17.6%

NA

64.3%

41.7%

50.0%

49.4%

Dollars

Average Revenue

per Unlinked

Trip

Highest Adult

Base Cash Fare

(a)

Average Adult

Base Cash Fare

(a)

Median Adult

Base Cash Fare

(a)

Lowest Adult

Base Cash Fare

(a)

Systems with

Peak Period

Surcharges (a)

Systems with

Transfer

Surcharges (a)

Systems with

Distance/Zone

Surcharges (a)

Systems with

Smart Cards (a)

Systems with

Magnetic Cards

(a)

a) Based on a sample of systems from APTA 2011 Public TransportationFareDatabase

b) Includes fare revenues for other modes not listed, $374.1 million

Table 1.1: Passenger Fares by Mode, Report Year 2010 (Dickens, Neff, & Grisby, 2012)

20

passes in bulk to local employers to be distributed to their employees. In their most basic form,

a company contacts the agency, orders a certain number of passes, and pays for them in advance

with money that has been collected from the employees that requested the passes. Most often

this is done through payroll deduction, which allows both the employer and the employee to save

money on their taxes (see Section 2.1 and Appendix A for more details). The passes are sent to

the employer's office and are distributed, or in the case of a reloadable smart fare card, the card is

automatically updated. This basic relationship is shown in Figure 1.1 below. In some cases, the

employer does not collect the cost of the pass from the employees or they only collect a fraction

of the cost as a benefit to the employee. The transit agency and-employers may also use a third

party who administers the process and takes care of distributing the passes to employees, or offers

a transit debit card or voucher instead. Employees, employers, transit agencies and society all have

something to gain from the effective implementation of employer pass programs.

Place order, pay in advance

E

Mail or auto-renew passes

oyer

Passes distributed

Paid

through

payroll

deduction

in advance

<:~ylee

Figure 1.1: Basic Employer Pass Program Structure

If an employee can purchase a pass using pretax payroll deductions and/or for a reduced

(subsidized) price from his employer, the employee is receiving a heavily discounted price. He

also has the additional benefit of receiving his pass through a subscription service; he signs up

once at the beginning of employment or is automatically "opted-in", and then he receives his pass

21

each month until he cancels.

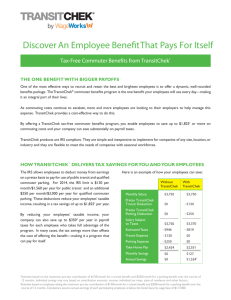

The employer also benefits from this arrangement, as there are also corporate tax incentives

for providing a deduction in its employees' taxable income. The employer can also benefit from

providing a subsidy, as the subsidized amount is not subject to payroll taxes, similar to healthcare

(see Appendix A for sample tax calculations), so this may be an effective alternative to offering

an employee the same amount of money as a salary increase (ICF Consulting, et al, 2003).

Additionally, promoting transit through a pass program can allow employers to manage limited

parking by reducing demand. There are three instances in particular where this is an enormous

benefit for employers. First, this allows new companies to avoid building large parking structures

or parking lots, which can be prohibitively expensive both in terms of construction and in terms of

paying for and navigating zoning laws and parking ordinances. Second, employer pass programs

allow growing companies that are quickly running out of parking spaces an inexpensive and easy

way of convincing employees to use alternative transportation, and can save them the cost of

acquiring more parking spaces. Finally, for large, well-established companies that have ample

parking, pass programs can divert employees from driving and parking, and thus these spaces

will remain open for customers, employees at nearby businesses, and visitors to park, possibly

even providing some additional revenue. Employer pass programs also allow an employer to send

a strong message that they are dedicated to helping their employees get to work and that they

care about supporting transit, decreasing traffic and/or parking, and increasing the livability of the

communities where they are located. In some cases, employers may also participate in a pretax

transit program to comply with city or state regulations.

Transit agencies can also benefit greatly from employer pass programs. Even if an employer

does not offer any additional subsidies, the convenience of the subscription service alone may be

enough to encourage employees to pay full price for a pass each month without using the service

enough to justify the full price. For example, if an employee must make a separate decision to

purchase a pass each month at full price, presumably each month she will consider how often she

plans to take transit. If her estimated cost of paying each day will be less than the price of a monthly

22

pass then she may not buy the pass. However, if she is enrolled in a subscription service she will

generally not make this decision month by month. There may be some months where she is on

vacation, working from home, or for some other reason she does not use transit as often as she does

in normal months. For such employees, the value of not having to remember to purchase a pass

each month and the convenience of not paying their cash fare day-to-day in the "off" months is

worth the extra price of the subscription in these months. Additionally, the pass program produces

savings by lowering the costs to the transit agency associated with cash handling and individual

fare collection.

For the employers that offer passes pretax, or those who offer a subsidy or a transit cash-out, the

benefit to transit agencies may be even greater. The pretax savings alone are a significant discount

to employees. Appendix A shows that the employee could save as much as 40% of the value of the

pass by receiving it pretax. A company can then choose to increase that discount to the employee

by offering a subsidy. For example, if a company subsidizes passes by 50%, instead of paying

the full $70 per month for a pass, an employee could purchase a pass for $35 (and if the pass is

purchased pretax, it would actually be less than $35 in out-of-pocket money). At typical transit

fares, this will pay for itself in less than 9 days, which may be worthwhile if the employee uses

transit occasionally, or on nights or weekends. In this case, the transit agency will receive the full

$70 pass price, even if the employee is not using the full amount. This subscription service may

also provide greater insulation from fare increases since the increase will not be as burdensome

for the employee if it is paid for with pretax dollars. Additionally, employees may come to enjoy

the benefit of getting a transit pass each month and will find it burdensome or even may forget to

cancel the subscription while they continue to have the cost deducted from their paychecks.

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) in the Boston region offers several

different avenues through which customers can pay for rides. There are single-ride fares, which are

a flat rate regardless of the time, origin or destination, and are higher for those who pay cash-onboard or with a paper magnetic-stripe CharlieTicket (as opposed to a plastic "smartcard" called a

CharlieCard). There are monthly passes, student semester passes, all day and weekly unlimited

23

passes, and a reduced price pass for seniors and persons with disabilities.

The complete list

of pricing for each fare type is shown in Appendix C for both before and after the July 2012

fare increase. All of these passes provide many options for transit riders throughout the Boston

metropolitan area, and riders can choose from a variety of options based on their own personal

transit usage (Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 2012a).

MBTA customers also have a wide variety of choices when it comes to paying for a pass

or single-ride fare. There are MBTA fare vending machines located at MBTA stations through

which customers can buy single-ride fares or passes. Some will purchase a single ride on a ticket,

and others who have reloadable plastic smart CharlieCards can simply add value to these cards

which are deducted each time a customer taps onto a bus or into a subway station. There is

also a CharlieCard store at Downtown Crossing station, and customers can purchase or reload

their CharlieCards on the MBTA's website. Bus passengers can reload value onto their cards or

purchase a single pass with cash onboard using the bus fare box, and commuter rail passengers can

buy single-rides or passes from their conductors or at the ticket window of commuter rail stations.

Recently, commuter rail passes and single-ride commuter rail fares became available for purchase

on customers' mobile phones, and they can also pay for parking at a commuter rail station through

their phone. Some local convenience stores even carry MBTA tickets and passes (Massachusetts

Bay Transportation Authority, 2012a).

The MBTA's Corporate Pass Program is a subset of the MBTA's monthly pass option. The

program was first established in 1974 as a means to reduce inefficient fare payment methods,

increase transit usage, and allow an avenue for employers to contribute to employee's transit

commutes. LinkPasses (unlimited monthly passes for all subway and local bus trips), monthly

Bus Passes (both local and express), commuter rail and commuter ferry monthly passes are all

available through the MBTA's Corporate Pass Program. Commuter rail 10-ride tickets, can also be

purchased through this program, though these tickets only account for 2% of the Corporate Pass

Program sales revenue. The payment options of the direct Corporate Pass Program are somewhat

limited since this program requires employees to order passes through their employer. On average

24

in 2012, the Corporate Pass Program sales brought in $11.5 million per month in fare revenue to

the MBTA (Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 2012b).

Monthly passes are a large source of the MBTA's total fare revenue, with 47% of sales revenue

coming from monthly passes. Within this group of monthly passes, 57% of sales are through the

Corporate Pass Program (or 27% of total sales revenue). This relationship is depicted in Figure

1.2 (Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 2012b). However, this 27% is not indicative of

all employees that are purchasing fares pretax through their employers. There are other options

offered by third party benefits providers (explained further in Section 2.1), including flex spending

accounts, vouchers and transportation debit cards. A rough estimate of the penetration of these

indirect programs is performed in Chapter 3, and by assuming the same distribution of pass

types and participation rates among these employers, the total revenue from these other options

is estimated to be between 3% and 8% of the MBTA's total revenue, or between $1.27 million and

$3.24 million per month (see Section 3.3.2). When added to the 27% of revenue obtained from

the subscription Corporate Pass Program, the total revenue from employer pretax programs can be

estimated at approximately 30-35% of the MBTA's revenue or between $12.8 million and $14.8

million per month. To clarify, the 27% of direct Corporate Pass Program revenue does include those

who purchase subscription monthly passes through third party providers, but does not include any

passes purchased through vouchers or debit cards, or reimbursed through flex-spending accounts.

The overall breakdown of MBTA revenue is shown in Figure 1.2.

25

12-17%

F

Estimated

Third-Party "Other"

Corporate Revenue

3-8%

(d)

7

(a) Single fares, weekly and daily passes; includes those purchased through third-party vouchers,

flex-spending accounts or debit cards.

(b) Includes third-party monthly subscription passes.

(c) Includes reduced fare senior passes, student semester passes, and third-party vouchers, flexspending accounts or debit cards.

(d) Estimated here as a range based on analysis in Section 3.3.2.

Figure 1.2: Monthly Pass Sales and Corporate Monthly Pass Sales as a Percentage of Total Sales

Revenue

In light of all of the potential benefits associated with an employer pass program, this study

aims to investigate the current MBTA Corporate Pass Program to better assess and quantify those

benefits. Up until this point, the MBTA has had limited knowledge of how individual employers

were implementing the Corporate Pass Program. It is not only useful for the MBTA to gain an

understanding of how the pass is being priced by different employers, but it is also useful to see

which employers are participating, how participation varies across employers, and how the use

of transit varies among employees of different companies. Additionally, the recent 23% acrossthe-board fare increase provides an opportunity to study the impacts of a fare increase on pass

26

purchases-both Corporate and Non-Corporate-and the comparative change in usage of these

passes. All of this information can help the MBTA to better understand how beneficial the program

is, how it ranks compared to other programs in the country, and how to further adapt the program

in a way that will increase revenue and transit usage, along with customer satisfaction.

1.2

Problem Statement

The MBTA has not recently quantified the benefits of their Corporate Pass Program. The first

step to quantifying the value of the program is to gather more information from the companies

that participate in the program. It is crucial to learn which companies participate, where they

are located, how many of their employees participate, if they offer the pass pretax, if they offer

a subsidy, and if they have similar policies for parking. It is also important to gather feedback

from these employers to aid in the assessment of the program. The next piece of the problem

is to determine not only how many people are participating in the program, but also how often

they are using the transit system. The MBTA cannot know how much additional revenue they

are getting from this program if they do not see how the usage of Corporate Pass Program riders

compares to Non-Corporate pass holders. Intuitively, the average Corporate Pass holder will use

transit less often than the average Non-Corporate pass holder since the lower price of the Corporate

Pass will attract additional people to the program who use transit less often. An investigation is

necessary to see if this hypothesis is actually correct and, if so, to what extent. The recent fare

increase also offers the opportunity to see if the Corporate Customers were less affected, as one

might hypothesize. The third piece of this problem is to determine how different characteristics

of the employer affect employer participation, employee participation, and employee transit usage.

Determining the characteristics of the most successful corporate relationships will allow the MBTA

to further shape the program or target advertising to their benefit.

27

1.3

Research Objectives and Methodology

The research methodology consists of three tasks that focus on each of the three research

objectives:

1. To gather more information about the current program and its participants.

2. To investigate the usage of Corporate pass holders as compared to Non-Corporate pass

holders.

3. To determine which factors influence employee participation and employee usage.

1.3.1

Employer Practice Survey

A survey was distributed to all of the MBTA's Corporate Pass Program employer contacts with the

intention of gathering more information about how the Corporate Pass Program is implemented

and utilized at various companies around the Boston area. The survey was conducted primarily

during the months of July 2012 and August 2012, with a second attempt sent out by Edenred-the

company that the MBTA hires to code the CharlieCards and tickets and fulfill orders-in October

2012. The survey was conducted via e-mail, and the respondents were given two response methods:

a link to an online Google Form survey, and an option to reply to the e-mail. There were a total of

564 responses, and about 72% of those responses were via the Google Form while the remaining

28% were e-mailed. The response rate was approximately 40% by company, and these responses

represented about 50% of all active CharlieCards in the Corporate Program.

The survey questions are listed in Appendix B. The responses were linked to the employer's

ID number, and the respondent's name and email were requested to facilitate follow-up questions.

Two respondents did not provide their company name or the respondent's name. Those results

were not included in the survey since we could not associate the responses with a location and also

because there was no way of knowing if these responses were duplicates of other responses (since

the survey was sent a total of three times).

28

A second effort was made to determine if the largest employers in Boston and Cambridge who

were not listed as direct customers of the MBTA were using a third-party benefits provider, or if

they were choosing not to use the program at all. These results should aid in determining how

many of the "non-Corporate" passes not listed in the MBTA's Corporate Pass database are actually

being reimbursed by an employer or purchased with an employer-provided transit-only debit card.

1.3.2

Corporate Pass Holder Usage Analysis

MBTA customers can gain access to the MBTA system in one of four ways: a plastic smartcard

called the CharlieCard, a paper ticket called a CharlieTicket, cash on board, or the most recent

method, which is only valid on the commuter rail and ferry system, mobile smartphone-based

ticketing. Corporate Pass holders receive CharlieCards if they are subway and/or bus riders only,

and these cards reload the monthly pass value automatically each month as long as employees do

not opt out of the program. The Corporate Pass is the predominant subscription service. Individuals

can sign up online, but the process is burdensome. Corporate commuter rail and ferry riders receive

a new paper CharlieTicket every month since the commuter rail and ferries do not have automated

fare collection systems and rely on visual inspection by conductors. The paper tickets also have a

magnetic strip that can be used on the central subway system, and the higher fare monthly ferry or

commuter rail pass also allows customers to use unlimited bus and subway services.

Since Corporate commuter rail and ferry riders do not tap in on their trains or ferries like

subway and bus riders do, it is difficult to directly measure their exact usage of the commuter

rail and ferry system in the same way that CharlieCard usage can be measured. For this reason,

bus and subway pass holders are the most accurate sample for the usage portion of this analysis.

However, commuter rail pass usage on buses and subways was also measured to estimate the likely

differences between Corporate and Non-Corporate Commuter Rail usage.

The CharlieCard usage was determined from Automated Fare Collection (AFC) transaction

data provided by the MBTA (2012d). The pre-fare-increase transaction data was obtained for the

months of April 2012 through June 2012 and the post-fare-increase data was for the months of

29

July 2012 through November 2012. The data was queried to separate the Corporate customers

from the Non-Corporate customers using a list of Active Corporate CharlieCards (Massachusetts

Bay Transportation Authority, 2012e). The average usage and median usage for each group was

determined and compared.

The results from above provide usage data for both before the fare increase and after the fare

increase. Given that the price of a LinkPass increased from $59 to $70 on July 1, 2012, the price

elasticity of demand can be calculated by determining the percentage difference in usage divided

by the percentage difference in price. For both Corporate and Non-Corporate transit users, the

percentage difference in price was 18.6% (($70-$59)/$59 = 18.6%). The absolute level of the fare

hike experienced by Corporate Pass users who enjoy pretax payment and employer subsidies was

lower than the full fare hike, though taken as a percentage difference-as long as the subsidies

remain constant-it remained at 18.6%. The different changes in usage were determined and the

price elasticity of demand for both Corporate and Non-Corporate customers can be compared to

the overall price elasticity of demand for transit.

1.3.3

Influences on Participation and Usage

In the third major task, the results from 1.3.1 and 1.3.2 were combined to determine to what extent

company location, industry, and policy affected employee participation and usage. A regression

analysis was performed to determine the influence of the following characteristics on employee

participation and transit usage:

" Employer location

" Pretax Availability

" Employer subsidy level

" Employer Size

" Employer Industry

30

* Availability of Parking

" Parking Subsidy

" City-Wide PTDM Ordinances

Though there are other factors that influence employee participation and usage, such as

statewide programs (DEP, clean air, health impact) or federal tax changes (such as the recent

increase in the pretax limit), these factors could not be included in this study. Since this is a

Massachusetts-based program, there is no way to compare the differential effects of statewide

programs or national tax reforms.

Ultimately, the information that results from this study can be used to help the MBTA develop

improvements to the Corporate Pass Program and market the program more effectively.

1.4

Organization of This Thesis

This thesis is divided into seven chapters. Following this introductory chapter, Chapter 2 delves

further into the background for the research, including current literature and previous research on

commuter benefits programs, the history and current status of commuter benefits in general and

the Corporate Pass program specifically, and a comparison to other employer pass programs across

the country.

The analysis portion of this thesis is presented in Chapter 3, 4, 5 and 6. Chapter 3 investigates

the current status of the program as a whole by presenting the results of the employer pass

survey, and then aims to estimate the current total market penetration of the program. Chapter

4 contains the usage analysis methodology and results, which compare Corporate Pass usage to

Non-Corporate monthly pass usage over the months of April 2012 to November 2012. Chapter

5 revisits the employer survey results and uses this information, plus location and industry

information, to create a model to predict employee participation and monthly pass usage based on

employer characteristics. The goal of this chapter is to determine which employer characteristics

31

are correlated with Corporate Pass Program participation and employee pass usage so that the

MBTA can better tailor their marketing and develop strategies to help the program grow. The final

question of the employer practice survey, which asks for open feedback to the MBTA, is examined

analytically in Chapter 6.

Finally, Chapter 7 contains the conclusions and recommendations

resulting from the research presented in the previous chapters.

32

Chapter 2

Literature Review

This thesis aims to use data gathered through the employer practice survey and AFC data to analyze

and improve the current MBTA Corporate Pass Program. Before improvements can be suggested,

past research must be reviewed and the current program structure must be analyzed and compared

to existing employer pass programs elsewhere. This chapter reviews the recent literature on transit

employer pass programs in the United States, the history of corporate commuter benefits in general,

and the MBTA's current fare structure and how the Corporate Pass Program fits into that structure.

It also explores employer pass programs offered in four other U.S. cities for comparison.

2.1

Commuter Benefits Overview

The term "Commuter Benefits" refers to "transit or vanpool benefits and parking cash-outs, which

provide financial incentives not to drive alone" (ICF Consulting, et al, 2003). This term is often

associated with, and sometimes confused with, "Transportation Fringe Benefits", which is the

"term used in tax legislation to refer to benefits for qualified parking, transit, and vanpool expenses"

(ICF Consulting, et al, 2003).

An important aspect of commuter benefits is that they only include benefits provided to

employees by employers. There are several different options for employers to provide transit and

vanpool benefits. One is for the company to cover the full cost of the benefit. The employer does

33

not incur payroll taxes for the benefit amount and the employee does not incur federal income or

payroll (and in some cases, state) taxes on this amount, so long as the amount is below the IRS

designated limit. The second option is for the company to offer a pretax benefit of the entire cost

of the pass (up to the pretax limit) which is taken out of the employee's paycheck before payroll

taxes are applied. The employees save federal income and payroll taxes on this amount, and the

employer does not pay payroll taxes on the deducted amount. Finally, the employer can offer a

partial subsidy so that the employer and employee each pay a share of the pass on a pretax basis.

See Appendix A for example tax calculations, which show what these savings can actually mean

for employees and employers. A final option is a parking cash-out, in which all employees receive

the value of the free parking as taxable income and then the individual employees decide whether

or not to pay for parking. Unlike the three previous options, parking cash-outs do not offer any tax

savings since the value of the cash-out is taxable for both the employer and employee. The law

does allow tax savings, however, if instead of choosing the cash option employees opt to use the

value of the parking space towards transit or vanpool expenses and the expenses are deducted from

their paychecks as described above (ICF Consulting, et al, 2003).

Commuter benefits can be provided through several different avenues. The MBTA Corporate

Pass Program is an example of an employer pass program where the agency distributes passes to

the employer and the employer pays the agency. Another option is vouchers, which employees

receive from their employers and can redeem when purchasing transit tickets in person. Vouchers

are becoming outdated, however, since many ticket sales are now being done via vending machines,

online or via mobile phones. A more recent version of vouchers is a transportation-only debit card,

which will only work at transportation merchants. Each merchant that accepts credit cards has

a unique merchant ID, and transportation debit cards will only work when those merchant IDs

contain the string that is unique to transportation merchants. These merchants can include ticket

windows, vending machines or parking garages, but do not include convenience stores which also

sell transit passes. A third type of benefit is reimbursement through a flex-spending account, which

can also be linked to a debit card (Commuter Check, 2012a).

34

2.2

History of Commuter Benefits

Prior to 1984, free parking provided by employers was considered a taxable fringe benefit.

However, this was not enforced by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), reportedly because they

could not determine a basis for the value of the benefit. Other benefits, including transit and

vanpool, were not treated as taxable fringe benefits and were therefore tax-exempt. The 1984 Tax

Reform Act aimed to fix this ambiguity, but in doing so adversely affected transit and vanpool

riders by making parking the only tax-exempt "qualified transportation fringe benefit". Transit

passes were considered "de minimis" fringe benefits, meaning that transit benefits were allowed to

be offered tax-free to employees as long as they were of small value ($15 per month or less, later

adjusted to $21 per month). If the benefit exceeded that value, it would be taxed for the full value

(ICF Consulting, et al, 2003).

This policy was altered eight years later when Congress passed the Energy Policy Act of 1992,

which expanded the term "qualified transportation fringe benefit" to include transit and vanpool.

Limits were still placed on these benefits, and there was still a large disparity in these limits

between parking and transit or vanpool. Employee parking was tax-free up to $155 per month

while transit and vanpool use was tax free up to $60 per month (ICF Consulting, et al, 2003).

In 1993, the Clinton administration released a U.S. Climate Change Action Plan which called

for legislation which provided workers the option of receiving the cash value of employer-paid

parking as an incentive to reduce single-occupancy vehicle commuting. Though this plan was

never enacted, it brought attention to parking cash-outs as an option for employers seeking to

reduce parking demand (ICF Consulting, et al, 2003).

The transit and vanpool limit rose slightly to $65 per month in 1995, and two years later

the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 amended federal tax code and allowed qualified parking to be

offered in lieu of a salary increase. Up until that point, federal tax code prohibited offering any

qualified transportation fringe benefit in lieu of salary, and required that transportation benefits

be offered in addition to an employee's taxable salary in order to maintain the benefit's tax-free

status. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 removed this major disincentive to parking cash-outs and

35

gave employers the ability to offer taxable salary increases in lieu of parking benefits while still

maintaining the tax-free status of the parking benefit for those who still chose to park. In 1998, the

Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-2 1) allowed employees to receive a cash-out

for any transportation benefit, not just parking, and it also raised the transit/vanpool cap to $100

per month effective in 2002. Parking benefits also rose to $175 per month (ICF Consulting, et al,

2003).

Commuter benefit limits continued to rise gradually in accordance with the consumer price

index until 2010 when transit and vanpool benefits were increased to match parking benefits at

$230 per month for each. The disparity was re-introduced in 2011 as transit/vanpool benefits

were reduced to $120, and then transit benefits were restored to be equal with parking at $245 per

month each in 2013. In 2009, bicycle commuters became eligible to receive up to $20 per month in

tax-free reimbursements from their employers for the purchase, maintenance and storage of their

bicycles (Internal Revenue Service, 2013a-i). See Figure 2.1 for a summary of the historical values

of the tax-advantages for transportation benefits.

$300

$250

$200

C

$5

S$150

-Parking Benefit Cap

-Transit/Vanpool

Benefit Cap

E

-Bike

Benefit Cap

$100

$50

$0

-

-

--

-F

e

r4

Tr0

IN

0

r4

0

0

C4

0

CN

N4

0

I

Figure 2. 1: Transportation Benefits Caps From 1992 to 2013

36

2.3

Evaluating and Improving Commuter Benefits Programs

There are many ways to measure success of a commuter benefits program, and an agency

must determine which methods are most valuable to them.

TCRP Report 107: Analyzing the

Effectiveness of Commuter Benefits Programs, states five measurable outcomes, listed below in

order of increasing complexity:

1. Awareness

2. Participation

3. Travel behavior changes

4. Transit agency impacts (ridership, revenues, and costs)

5. Regional impacts (vehicle travel and emissions)

The first method through which a program can be assessed is program awareness. Surveys in

several parts of the country have found that employees may be less aware of programs than one

might expect. For example, a 2004 survey in the New York City metropolitan area revealed that

just over half of respondents could not answer definitively whether or not their employer offered

any programs to aid with commuting costs (ICF Consulting, et al, 2005). A complete survey to

represent all employers and employees in the Boston area was not feasible for the purposes of this

research, but the findings from previous studies serve as a warning that it is likely that awareness

is not as widespread as an agency might assume.

Program participation consists of both employer and employee participation.

For some

employer pass programs, determining employer participation is simple if they maintain a customer

database. However, since part of the MBTA's program involves third-party administrators, the data

is often not fully available and an exact number is not easily attainable. This study estimates the

penetration of the MBTA program using various methods (see Chapter 3). Employee participation

among companies in the direct MBTA Corporate Pass Program is easier to determine as the number

37

of individual passes are known based on billing records. The employers that are known to be

enrolled in the program were surveyed, and employee participation rates at each company (based

on the reported employee totals) and generally across the region was determined (see Chapter

3). Employer characteristics such as location, worksite size, employer discounts (meaning full

or partial subsidies), and industry type may all lend additional information as to which types of

companies are participating now and how to best expand the program in the future.

Travel behavior changes include the number of new transit trips (peak and off-peak), changes

in transit mode share, and changes in the vehicle trip rate (VTR). The employer survey will glean

some information about these changes from employer to employer based on program availability.

Transit trips can be compared among employees of different employers to see how different

employer characteristics are influencing these changes, and also can be compared to MBTA riders

who are not enrolled in the Corporate Program. Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP)

Report 107 found-through a survey of 21 transit agencies, commuter organizations and thirdparty benefits providers in 12 regions across the United States-that transit ridership generally

increases 10% or more at worksites offering commuter benefits programs that include transit

passes. The increase was seen across virtually all of the 21 surveys, though the amount of increase

varied greatly. Half of the surveyed agencies and organizations reported a 10-40% increase, though

some increases were greater than 100%. The presence of a commuter benefits program not only

attracts new riders but it also generally increases ridership for existing riders. This study also found

that the new riders were primarily previously single-occupancy-vehicle drivers (ICF Consulting, et

al, 2005).

Transit agency impacts include ridership, revenues, and costs. This is especially interesting for

this research because midway through 2012 there was an MBTA fare increase so the fare impact

could affect Corporate and Non-Corporate customers differently. Records of fare revenue (both in

dollars and units) and ridership over time are instrumental in gaining insight into this program's

effectiveness at partially insulating employees from fare increases.

38

Regional impacts, such as vehicle travel and emissions, are very difficult to both measure

effectively and to relate directly back to a specific program or event. For the purposes of this

study, they are not considered. Some commuter benefits companies have developed tools to help

employers estimate the environmental and financial impacts of such a program. One example,

shown in Figure 2.2 below, is available on the Commuter Check@ website.

Results

The number of miles that $1000.00 worth of commuting will buy is 5221 mtles

From spending $1000.00 commuting, your company produces 25687.32 pounds of

carbon yearly.

From spending $1000.00 commuting, your employees save $3300.00 in taxes annually

by commuting.

From spending $1000.00 commuting, your company saves $80.00 in taxes annually by

commuting.

From spending $1000.00 commuting, the cost to drive the same distance annually is

$26541.11

The amount of carbon produced by driving the same amount in miles for 1 year is

46802 pounds

The annual savings from commuting and not driving to work is $14545.11

The annual carbon savings from commuting and not driving to work is 21115 pounds

By saving 21115 pounds of carbon by not driving is equivalent to the amount of carbon

saved by 246 tree seedlings that have been growing for 10 years.

Figure 2.2: Commuter Check@ Company Savings Calculator

For marketing purposes, it is helpful to know which employers will be most receptive to

these benefits. TCRP Report 87: Strategiesfor Increasing the Effectiveness of Commuter Benefits

Programsexplores the characteristics that contribute to success (close proximity to transit, many

39

employees already using transit, the company values commuter benefits, size, and a stable

corporate environment).

Unsurprisingly, employers situated close to high-quality transit are

very receptive to these programs, making downtown areas strong targets for commuter benefits

marketing. Futhermore, employers who have many employees currently using transit or vanpool

may be very receptive, even if they are not located close to "high-quality" transit. Another factor

that is more difficult to measure is if the employer sees the value in commuter benefits. Employer

size can also be influential, though there are some trade-offs. Larger employers may be more

receptive because employers with 100 employees or more often have a benefits or "work-life"

manager who serves as a good point of contact and may help to promote the program within

the company. Also, state and local regulations often require employers over a certain size to

offer pretax transit benefits, as with the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection

regulation or the ordinances in Cambridge, MA and San Francisco, CA (Massachusetts DEP,

1797; Cambridge Community Development Department, 1998; City and County of San Francisco

Board of Supervisors, 2008). On the other hand, smaller companies often do seem more willing

to implement the program since these companies have fewer levels of decision-making authority,

generally only one worksite, and lower administration costs. So it seems that larger employees

are good targets for marketing because they bring greater participation rates and more employees

into the program, but smaller companies with fewer levels of management may be easier to work

with and can make the decision to join the program more quickly. Finally, employers who are

currently facing financial problems or mergers, or who have unfilled employee positions may not

be receptive to a commuter benefits program until they become more stable (ICF Consulting, et al,

2003).

Marketing commuter benefits can involve some creative approaches. Although the end-users

are the employees, the marketing must ultimately target employers since they are the ones who

decide whether or not their employees will have access to the program. Some agencies have

attempted marketing campaigns aimed a the general public and current transit users to "bug

your boss" for commuter benefits. This tactic also involves letting the public know when there

40

are changes in the program, such as an increased pretax limit. Of course, the other option is

to market directly to employers. Recommendations from TCRP Report 87 include developing

partnerships with business groups to reach employers. In Boston, this could include A Better

City Transportation Management Association (ABC TMA). It also includes maintaining an

extensive database of employers and sending out mailings or e-mails when there are program

changes. Creating highly professional materials for employers that are written specifically for a

business audience, as well as maintaining a professional and informative website are also key.

If these materials are not provided by the agency, then employers are responsible for providing

the necessary information to their employees which can become a barrier to participation (ICF

Consulting, et al, 2003).

2.4

History of the MBTA Corporate Pass Program

The Corporate Pass Program has been a staple of the MBTA's fare payment structure since the

1970s.

On March 1, 1974, two-thousand employees of John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance

Company become the first MBTA riders to purchase prepaid MBTA passes through payroll

deduction. One month later, all state employees working in Boston were allowed to enroll in the

program, followed by City of Boston employees, and eventually the program grew to many other

companies in and around the city to become an integral part of the MBTA's fare payment system.

Since this was prior to the Tax Reform Act of 1984, the fare sales for the original Corporate

Pass Program could be deducted pretax from employees' paychecks. The employees experienced

additional savings through this program as well. There were three pass types available: a $105 per

year pass for commuters whose one-way commute on the MBTA cost $0.25, a $189 per year pass

for commuters who rode a $0.20 feeder bus to the subway, and a $210 per year pass for those with

a $0.50 one-way commute (the Riverside and Quincy lines as well as some Express Buses). The

more expensive express buses or commuter rail lines were not included in this original program.

The price of the pass was calculated based on 42 five-day working weeks, so that an employee that

41

received five weeks of paid time off (vacation, sick or holiday time) would get an additional five

weeks of free commuting-a 10% discount (Fuerbringer, 1974).

The introduction of the Corporate Pass Program signaled the beginning of a movement away

from expensive and inefficient fare collection by token and cash. The goals of the Corporate

Pass Program were to reduce transaction times at stations and on buses, as well as to incentivize

more use of transit, especially off-peak, by introducing zero marginal cost pricing. The Corporate

Pass Program also established a mechanism for employers to contribute to their employees' transit

commutes, analogous to provision of parking, through improved convenience, financial incentive,

and cultural "nudging". It was also believed that the program would improve the stability of

ridership when fares increase, and improve the attractiveness of transit in general (F. Salvucci,

personal communication, May 2, 2013).

In the mid-1990s, the MBTA embarked on a major advertising campaign which lasted for

several years. This campaign involved the purchase of employer databases and mass mailing

targeted to employers near MBTA stations. This effort doubled the number of MBTA clients

from 900 to over 1,800 (ICF Consulting, et al, 2003). In December of 2006, the MBTA introduced

the CharlieCard, along with a new web-based ordering and tracking system for the Corporate Pass

Program. This made the program easier for customers to use, and CharlieCards could simply be

reloaded each month without mailing new cards to the customer. Commuter rail and ferry passes

are printed on paper tickets, and still need to be mailed out. The new web-based system not only

made ordering easier, but it also made it easier for customers to access their receipts which can

be used towards auto insurance discounts through some insurance companies (Massachusetts Bay

Transportation Authority, 2012a). Given the improved user-friendliness of the system and the

passage of time since the last advertising campaign, it is time for a new initiative, which should be

repeated each year to maintain visibility.

The MBTA contracted the printing and activation of passes and CharlieCards to Cubic

Transportation Inc., beginning in 2009 when Cubic moved into the building that had been used

by the previous contractor. Although the contract meant less day-to-day work for the MBTA, this

42

arrangement turned out to be vulnerable to fraudulent use. In May 2011, it was discovered that

two employees of Cubic had been printing and activating passes without entering these passes into

the MBTAs system. Then, the passes were being sold on Craigslist for a discounted price. All

told, the culprits printed 20,000 tickets worth approximately $4 million. Although the scheme was

uncovered and the criminals were prosecuted, this criminal activity brought some negative press

to an otherwise very positive program (Roman, 2011). These events also allowed the MBTA to

terminate its arrangement with Cubic Transportation and begin their current contract with Edenred.

In July 2012, the MBTA implemented a 23% across-the-board fare increase, which raised the

price of a monthly local bus pass from $40 to $48, a LinkPass (unlimited bus and subway) from $59

to $70, and raised commuter rail passes on a zone-by-zone basis. Additionally, single-ride fares

were increased from $1.25 to $1.50 for local bus and $1.70 to $2.00 for rapid transit (Massachusetts

Bay Transportation Authority, 2012c). In light of this fare increase, the MBTA is reexamining the

existing programs-including the Corporate Pass Program-to see if there is any potential for

increased revenue, if the program should be modified, or if the program should be enhanced so as

to minimize the impact of future fare increases and service cuts.

2.5

MBTA Fare Structure and Current Corporate Pass

Structure

2.5.1

MBTA Fare Structure

The MBTA offers both single-fare payment options and monthly passes (see Table 2.1). Single

fare prices differ based on whether the customer is paying with a paper CharlieTicket or a plastic

reloadable CharlieCard. Bus passengers may also pay with cash-on-board for the same price as a

CharlieTicket. Commuter Rail and Ferry passengers can only pay with CharlieTickets, cash-onboard or mobile ticketing. Customers who pay cash-on-board on the Commuter Rail are subject

to a $3 surcharge. For further details on Commuter Rail and Ferry pricing as well as fare increase

43

information, see Appendix C.

Si ngle Ride

ChiarlieCard

ChiarlieTicket

Senior/TAP/Student

Bus

Rapid Transit Bus + Rapid Transit

$1.50

$2.00

$0.75

$2.00

$2.50

$1.00

Pa sses

Bus

7-)ay

M )nthly

Se nior/TAP/Student

$18.00

$48.00

$28.00

Rapid Transit Bus + Rapid Transit

$18.00

$18.00

$70.00

$70.00

$28.00

$28.00

Commuter Rail and Ferry Single-Ride

Commuter Rail

$2-$ 11

Commuter Ferry

$8-$16

$2.00

$4.50

$1.00

Monthly Passes

$70-$345

$262

Table 2.1: MBTA Single-Fare and Pass Pricing

2.5.2

Corporate Pass Program Structure and Third-Parties

The current Corporate Pass Program structure is depicted in Figure 2.3. The MBTA currently has

a contract with a local employee benefits company called Edenred to help administer the program.

This company receives the Corporate Pass orders from the MBTA, encodes the Charlie Cards

and distributes the passes to the 1,335 companies that participate in the program. On average,

a total of 116,700 employees receive passes through the MBTA Corporate Pass Program each