Caribbean Community Regional Aid for Trade Strategy 2013–2015 Caribbean Community Secretariat

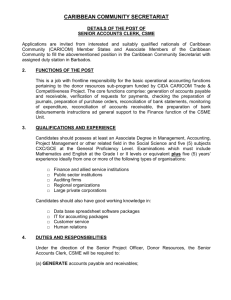

advertisement