T A S C

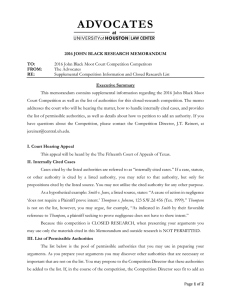

advertisement