N . 12-20784 ________________

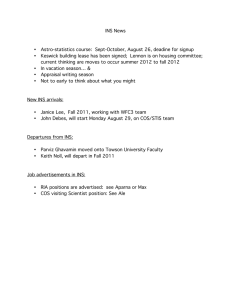

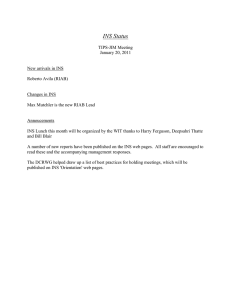

advertisement