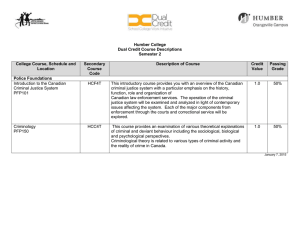

N . C11-0116-1 ________________

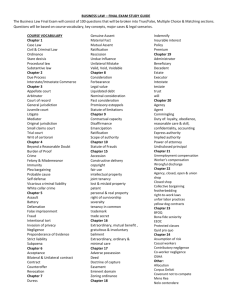

advertisement