Document 10897547

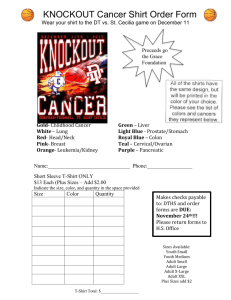

advertisement