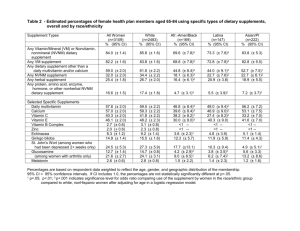

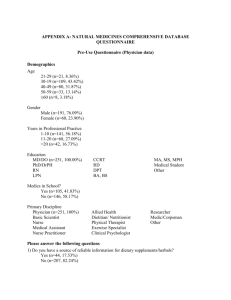

PREVALENCE OF NONVITAMIN, NONMINERAL SUPPLEMENT USAGE AMONG

advertisement