INVESTIGATION OF ACCULTURATION CHANGES IN FOOD INTAKE

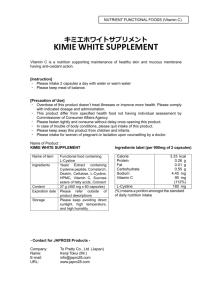

advertisement