A PROFILE OF DIETARY SUPPLEMENT USE OF by

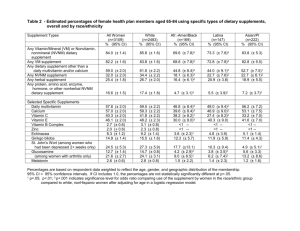

advertisement