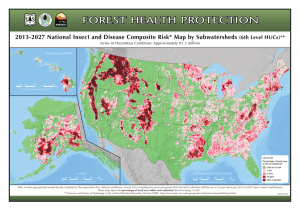

Article ADAPTIVE WATERSHED PLANNING AND CLIMATE CHANGE

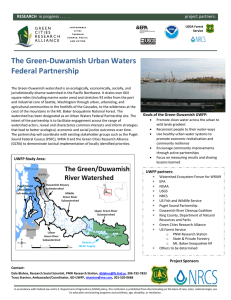

advertisement