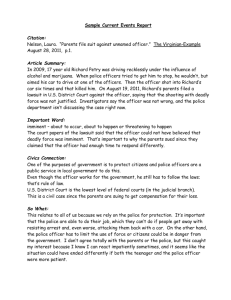

THE OF POLICE ABUSE AUTHORITY

advertisement